25 January, 2016

This Immortal (aka ...And Call Me Conrad) by Roger Zelazny

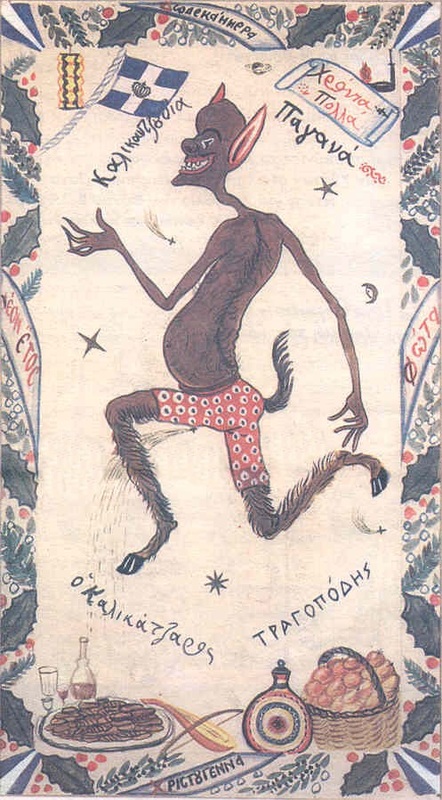

1. This book has a problem: it is referential to a fault. A lot of paragraphs draw parallels to a wide array of references—ancient Greek myth, contemporary 1960s culture, and pop cultural references timed between the ancients and the 1960s. These references are so thick that it easily loses the reader at times. But never for too long. Zelazny always shows what the references mean, rather than telling, yet the references are still too much. They bog the reader down with questions of what the references mean: there are simply too many of them to allow any reader to know all of them. This fault moderately reduces my enjoyment of the book.

2. The other problem is major and can be stated more simply: Zelazny is concise to a fault. The plot is threadbare and the wonderfully witty dialogue almost too fast. Things happen quickly with little or no set-up or rise in tension. This makes everything seem quick and perhaps unplanned. Of course, the last three events—the dead man, the hot spot, and the black beast—are foretold by Conrad’s son Jason. But Jason shows up out of nowhere, the cannibals show up suddenly, and the black beast appears and is beaten before it has any real impact on the story or characters. This fault massively reduces my enjoyment in the book. I wanted to really explore some of the plot points, exist in them for a time, and contemplate some of their ramifications. Instead, I’m left wondering what effect the hot spot had on Hasan; the black beast is a quick, simple battle and I’ve no idea as to its significance to the world at large; the pipe playing happens so fast with no real transition to allow me to properly place the characters. In other words, things happen so quickly I’m still a bit unsure what is dream and what is plot. There is a balance to grasp here, that Zelazny doesn’t: too slow and the reader gets bored, too quick and the reader gets lost, though between too quick and too slow exists a wide gray area of pacing that I enjoy. Zelazny moves too quickly and this book doesn’t hold me the way Lord of Light, Zelazny’s later book, did. This quickness also makes events seem like deus ex machina at times, which is a negative. If he adds something to the reader’s knowledge of the world, you can bet that within ten pages, that new element will come by to save the day.

3. Now that those two unpleasantnesses are dealt with, I can move on to why I enjoyed this book. First, the writing is superb. Zelazny strikes a perfect balance here between beautiful and efficient language that kept me engrossed and enjoying even the referential sentences I didn't understand at all. I loved Zelazny’s writing here, full of consonance and internal rhyme, but not over the top. He also uses a lot of analogy to say things. One example is that the two shots of the elephant gun at the end are likened to the thunderbolts of Zeus. This analogy wonderfully keeps the mood of myth and mystery, while being a worthwhile description of what actually occurred.

4. Second, the characters are engrossing and distinct. Though the book tends towards quickness, ending up more a novella than a novel, the characters are well developed mostly through dialogue, but also through sparse use of Conrad’s psychic power. Zelazny uses dialogue to build the characters, rather than extensive backstory or an omniscient narrator’s description. The book takes the form of Conrad looking back on these experiences, telling them to the reader from his point of view. This let’s Conrad’s exposition of the characters really focus on the dialogue and actions of the others.

5. Third is the plot—it’s both a post-apocalyptic tale and a post-contact story. This combination seems odd conceptually, but Zelazny ties them together enough that my imagination runs wild. Again, the quickness steals some of the satisfaction I should feel at these two tales being woven together well, but there is enough in there that I greatly enjoyed the plot and the implications for planet Earth.

6. The main character is Earth, not Conrad. That’s really the whole gist of the book—what happened to Earth, what it’s like in the book, and the potentials it's left with at the end. This ties into the theme of adaptation. I don’t mean that in the ecological sense too deeply—to me the theme centers around Conrad adapting his tactics to fulfil his goals, and modifying his goals as a necessity. For instance, in the past Hasan, Phil, and Conrad bombed islands and killed the alien invaders in an attempt to galvanize a return to Earth by ex-patriots. However, they both realize that will never work and change their tactics. Phil becomes the consummate socialite, helping to establish and preserve a reason for some to stay on Earth. Conrad becomes a governmental official, helping to distinguish Earth as a unique entity—Earth for Earth’s sake, with all the warts and boils inherent in it. They both have changed to continue attempting to accomplish their goals of making the world better for humans. Their goals also change by abandoning the naive hope to work against the aliens, realizing instead that alien power and influence necessitates working with them. This adaptation requires a realistic appraisal of the situation and some deep changes in the characters. But they end up being successful only by subduing their earlier impulses for bloodshed: they destroy their earlier efforts in order to create a new balance.

7. This book is a wonderful read, partly because it is so short. Any longer and the quickness with which it dispatches plot points would’ve been overly trivial. The characters are strong: Conrad is a superhuman anti-hero, as is Hasan; Earth is a vibrant and damaged, the damage adding to the diversity and vibrancy; George the single-minded scientist; Ellen the socialite flitterer; Red the neophyte of a past iteration of Conrad. What little plot there is grips the reader and provides abundant space for the reader to fill in the blanks and spin their imagination to fantastic places. It’s all a single chapter, start to finish, and Conrad follows the action pretty closely. A worthy read, but not great. This shared the Hugo for best novel in 1966 with Dune, which is a better novel to me. But for a novella, this book is fun—especially the writing; for that writing I will forgive a lot. The novella category was added to the Hugo awards in 1968.

Labels:

1965,

Hugo Award,

Roger Zelazny,

Science Fiction

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg/640px-View_of_the_Acropolis_Athens_(pixinn.net).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment