Showing posts with label George RR Martin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label George RR Martin. Show all posts

23 August, 2015

73rd World Science Fiction Convention: Worldcon 2015: Sasquan in Spokane, Washington

Panel 1:

The Future of Short Fiction: Online Magazines Today

1. This panel was interesting, but more from a business perspective. Since I don't find business informative to my writing process, there's not much I can say here about this panel. The only take away is that the science fiction magazine is still alive and well, it's just online now.

2. My reading list from this panel:

Lightspeed Magazine, which won a Hugo later that evening.

Clarkesworld Magazine

Strange Horizons Magazine

Panel 2:

The New Space Opera

1. This panel was packed. Standing room only, and very little of that. The first argument was that space opera never fell out of production. The authors assembled believe there is not an inherent difference between old space opera and new space opera. Though much space opera fell out of popularity after the space operas of the 1930s and forties were deemed not literary enough, there were still authors writing good space opera and bridging the gap between then and now. Iain M Banks was a major bridge, and all the authors agreed.

2. Space opera was typically defined as exploring human emotions appropriate for opera, the story and writing serving to foster a sense of wonder, a large physical scale, a broad time period, and adventure and drama. I rather liked this definition that they gave, I think it's useful and informative. It fits my conception, and expands it as well: I hadn't previously thought about the emotional content of many space operas.

3. A theme of some of the comments was how to get away from the fascist or regal galactic empire so commonly a backdrop in space opera stories. Jokingly, one of the authors suggested the next new thing in science fiction would be "committee punk". But Ann Leckie quickly pointed out what they all agreed to: that she does not enjoy overly complex political committees in her day-to-day life, so why does she want to read about them? The conclusion was simply that we need a backdrop more honest to humans and life, but not boring or dreary. We have complex democracies, and yet the space opera is still caught in the feudalism of the past. At this point, a fan pointed out that from a long-term perspective on the history of humanity, really feudalism is king and has been the major governmental force for well over 90% of history. So, the problem I was left with was how to create a system that is honest to the complexities of human politics, but not bogged down in essentially reading minutes of committees.

4. There was a brief discussion about hard science fiction space operas. With Charlie Stross on the panel, that discussion was on point. He stated that he never finished his earlier trilogy because he had realized that there were inherent inconsistencies in the science behind his story. He walked away from it embarrassed, despite both volumes being nominated for Hugos. However, he acknowledged that he is attempting to use science that humans believe is possible in his new planned space opera trilogy. He intends to stay as scientifically rigorous as possible, to avoid the inherent contradictions of his last series. He made no value judgment between his scientifically-rigorous work and the work of others—he actually seemed to support other authors treating future science as if it was space magic. He felt that it was honest for somebody to include faster than light travel in their space opera, but exclude a pseudoscientific attempt at explaining it. We simply don't know how it would work if it could, therefore if you want to use it use it, but don't try to explain it.

5. In a lot of ways, the space opera comes out of the horse opera. This is most apparent in the series Firefly and Star Wars—especially A New Hope, which steals some shots from John Ford's The Searchers. A lot of the early space opera simply switched the horse to a spaceship, the six shooter to a blaster, the ten-gallon hat to a space helmet, and Main Street to Planet OK Corral. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but to me it seems lazy because it shows authors not really exploring the potential effects of their set pieces. For instance, I think a large part of the characterization of some of the major characters in science fiction comes from their interaction with their environment: whether that's being predisposed to keeping to themselves because they spend a lot of time on a very small spaceship, or Paul really learning who he is through experiencing and understanding the desert of Dune, or Elijah's life in the titular Caves of Steel creating an outlook in him that is negatively insular and xenophobic. These are just three examples, but there are hundreds of other examples of authors exploring, thinking about, and theorizing about their set pieces, their window dressing, to the point where it isn't a set piece or window dressing anymore: it's an integral part of the story, driving philosophy and ideas, and it has effects. For Charlie Stross, this means being as honest with science as he can. For Frank Herbert this meant allowing the desert to inhabit his characters, to change them deeply, rather then just having it be a desert planet because deserts are cool.

6. My reading list from this panel:

"Anything published by Iain M Banks will be worth your time and interest." Charlie Stross said this and much of the crowd and panel agreed. It seems the consensus is to read Excession, Inversions, Use of Weapons, and The Player of Games at least.

Charles Stross' own books Saturn's Children and Neptune's Blood (These are the ones that contradicted themselves), and his forthcoming novel, where he claims he doesn't mention singularity once.

Ann Leckie's Ancillary Blank series, which was already on my list.

Doc Smith (EE Smith) for the pulp foundation of the Space Opera.

Panel 3:

Demigods, Chosen Ones, and Rightful Heirs: Can Progress, Merit, and Citizens Ever Matter in Fantasy?

1. This was one of the worst moderating jobs I've ever seen. The moderator actively discouraged much of the more interesting questions and discussions because she couldn't allow others time to think—the silence of the room seemed to drive her mad and she kept trying to move things forward. She missed so much. All this after admitting at the beginning, "My day job is writing award winning historical fiction, like The Pirate's Secret Baby, available soon from such and such a press. So I don't know much about this topic and I'm going to let the other four really take the show." Then she proceeded to ask every question, time every answer, and allow only the minimum of discussion, as well as inadvertently insult two of the four panelists, shut down panelist comments, go off on tangents from statements its obvious that she didn't understand, and generally be in the way of the panel. That said, the four others on the panel had some fascinating ideas and opinions. I only wished that I could watch them all talk, rather than this sort of speed dating panel thing the moderator attempted. These notes will be short because the authors weren't allowed to really explore any of the ideas that they brought up.

2. One interesting idea was that humans are never existing alone, they're typically in a group. Therefore, perhaps narratives of a chosen group would be more honest to humanity then narratives of a chosen one. Because everybody works together, there is some complexity to a group dynamic that just isn't there in the typical chosen one narrative. Because everybody could work to their strengths, this could allow a wide diversity within the group. This seems much more based on reality than the chosen one.

3. Another interesting idea was that ensemble casts were a simple way to get away from the chosen one narrative. Different points of view would also effectively entice the writer to humanize some villains, demonize some heroes. This would effectively get away from a messiah, or the typical story ending of the hero taking back the throne that is theirs.

4. Katherine Addison was up for a Hugo that evening. Though she didn't win it, she had great comments: she finds it difficult to get away from the chosen one narrative, because it is so prevalent. It seems that in her mind, and the mind of most fans, the setting of fantasy is synonymous with a messianic narrative. This is fascinating, but was entirely unexplored. She ended with saying, "Think about what you read, think about what you write." And boy did that ever need to be said now.

5. Annea Lea stated that she was prickly with any rules in fantasy that something has to be done a specific way. She advocated variety in everything: story arcs, characters, settings, writing styles, etc. It was awfully exciting and persuasive because she argued that fantasy today does not embrace the variety and reality of humanity or history. By being so focused on the chosen one narrative, fantasy is digging its own grave.

6. Of course the elephant in the room that nobody talked about was A Song of Ice and Fire: instead of the chosen one, this is the chosen none; he has variety through an ensemble cast and different points of view; and it's revitalizing and repopularizing fantasy.

7. My reading list from this panel:

Katherine Addison's Goblin Emperor

Setsu Uzume's anthology Happily Never After

Mary Soon Lee's short stories & poetry

Panel 4:

Seiun Awards and Science Fiction in Japan

1. This was sad: at a time when the science fiction community is spending too much time spilling pixels over issues like merit, diversity, and how to judge a book, the international presentation of the Seiun Awards were attended by 21 people, including myself. I expected a ton of people in there simply to support the diversity inherent in Science Fiction. But no, it was a large, empty conference room capable of housing probably 300. Yet there were only 21 of us. The discussion was great though!

2. The Japanese government is currently studying science fiction, anime, and mecha by giving grants to the universities to establish departments to historically collect, collate, and document, as well as study these through the scholarly tactics of comparative literature, cultural anthropology, and human psychology. This has been going on for some time now. This scholarly research is prioritized and highly-regarded in Japan. They didn't really have time to talk about much of the actual research findings, but they did mention that where the western world calls the cyberpunk of today post-cyberpunk, lumping everything together, the Japanese scholars see at least three distinct generations of cyberpunk, and some argue for four.

3. There was the general agreement, as with all cyberpunk of the last 20 years, that we're living in the future that cyberpunk predicted for us. The example given was left-behind construction projects and buildings in the video game Second Life. These were simply left-behind because the players moved on to other games. Because of the textures, they still look brand new and sparkling and clean, but there is no habitation, no age, no pattern of memory worn into the textures, and their abandonment is completely strange.

3. A characteristic of cyberpunk today appears to be a focus on tangibility. But more important than that, is this sense of cyberpunk pushing itself out of its comfort zone. "It's one thing to write your strengths, but it never pays to get too comfortable in your writing," said 2015 Seiun award winner and founder of cyberpunk Pat Cadigan. And of the three stories that were discussed from this year's Seiun awards, at least two showed this. In brief, cyberpunk can be loosely classified by about five characteristics: a street smart anti-hero, an earthbound or near earth culture, a depressing dystopian future run by corporations, rain slicked neon-lit streets, and body modifications with invasive interfaces with the internet. Pat Cadigan's winning story, "The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi", takes place on Jupiter, breaking the earth-bounding typical of cyberpunk. Taiyo Fujii's Gene Mapper explores a happy future earth, instead of the dark, depressed dystopia typical to cyber punk. This shows cyber punk growing and embracing new tactics, techniques, and variety. How exciting!

5. My reading list from this panel:

Pat Cadigan's "The Girl-Thing Who Went Out to Sushi", which was already on my list.

Taiyo Fujii's Gene Mapper

Andy Weir's The Martian

More cyberpunk from today.

Hugo Awards Ceremony:

Watch them here, they're uploaded online. We were all laughing and in tears at points, there were some very funny people on stage. The winners are listed here. George RR Martin said, "I wish the internet did not have this horrible effect on the discourse. It tends to political toxicity and hardened battle lines."

Wired's post-award breakdown and recap of the kerfuffle.

Labels:

2015,

Andy Weir,

Ann Leckie,

Annea Lea,

Charlie Stross,

George RR Martin,

Hugo Award,

Iain M Banks,

Katherine Addison,

Mary Soon Lee,

Pat Cadigan,

Setsu Uzume,

Taiyo Fujii

06 August, 2015

A Song of Ice and Fire Series by George RR Martin

For Matt & Creed

This is about all five of the books in the Song of Ice and Fire series:

1. A Game of Thrones

2. A Clash of Kings

3. A Storm of Swords

4. A Feast for Crows

5. A Dance with Dragons

Because they are a continuous story and series, and they are so similar, I have chosen to talk about them as a whole instead of five separate books.

1. I find a distinction between a good writer who chooses words well and varies sentence structures interestingly, and a good storyteller—a writer who paces himself well, constructs the story in a clever way, and does not let a big story point become forgotten. Martin is the latter, not the former. For instance, the twincest is a big plot point, but it is never forgotten and never unimportant—and not in a sensational way, or not in a wholly sensational way. It is not a cheap, egotistical writer's trick, "Look at me! I will tackle even incest between twins! How courageous I am!" Rather, it is a major plot point and a fulcrum for the entire story. But the absolute best thing that George RR Martin does is his structure of sequential chapters from different characters' points of view. I have not seen this before in writing, so let me explain exactly what this is: in Chapter 28, Cat comes back from hearing that Tyrion probably attempted to murder her son, and ends up finding Tyrion on the road, so she kidnaps him; Chapter 29 is a royal tournament, told from the point of view of Cat's daughter; Chapter 30 concludes the royal tournament from Ned's point of view, and continues the thread of Ned's investigation; then Chapter 31 returns us to Cat and Tyrion, this time, however, the chapter is from Tyrion's point of view, with maybe two weeks to a month of time elapsed after he was kidnapped—there was as much time between his kidnapping and Chapter 31 as time spent in Chapters 29 and 30, which dealt with other story arcs. This is how the entire series is written. Every single chapter. This is brilliant and well done. I do not think I've come across somebody else who builds their chapters this way, and it's incredibly effective. This structure fits and maybe even encourages the complexity of the story. As a writer, I wonder at how much time Mr. Martin spends making sure that he has his facts straight, his chapters sequential, and his lore correct? This is complex stuff and he pulls it off. I would say 90% of that success is because of the fantastic chapter structure—he realized that with his complex plot, he would need this straightforward chapter system to keep everything legible.

2. On the other hand, the writing is not great. It communicates, and at times characters have their own voices, but on the whole its unremarkable. The writing begins in Book 1 as merely OK, then gets progressively better until the end of Book 1—but it never gets great except for these four paragraphs, which I think are stunning and beautifully written:

3. The female characters are strong, well written, and believable without pandering to a single sense of "femininity". This is achieved through having multiple female characters—Sansa is a demure dreamer, Cat is a dutiful realist, Lysa is a protective paranoid, Arya is a free spirit—the females are as varied as the males, and as important. I heard somewhere that he wrote the females by just writing characters, and their gender was almost incidental after that. I don't know if that's true or not. But, to me, it seems like they are all women, through and through—though maybe that's because of the varied spectrum of female characters presented.

4. A major complaint about the series is a lack of a moral, or driving central theme. I don't think that's fair. Partway through Book 3 I wrote my notebook, "There are consequences. I think this is an important distinction: the gods do not appear powerless, though not all powerful either, but there are consequences to gaining their favors or boons or help. Satisfying a desire requires sacrifice—acquiring a desire requires prioritization, sacrifice, skull sweat, self examination, open eyes, planning, and maybe some money." After five books, I do think this is the central theme: you can't shake your past and you have to sacrifice on the altar of the future. One character searches for truth and ends up executed because the truth concerns those who could execute him, and his past complicated matters. Cat looks for the hand behind the attempted assassination, but her past history seduces her into believing lies, and in her desire to satisfy her curiosity she sacrifices the realm on the altar of the future. Every story arc, every character, every plot point comes back to the necessity of sacrifice. Sometimes the consequences are foreseen, and sometimes they are not.

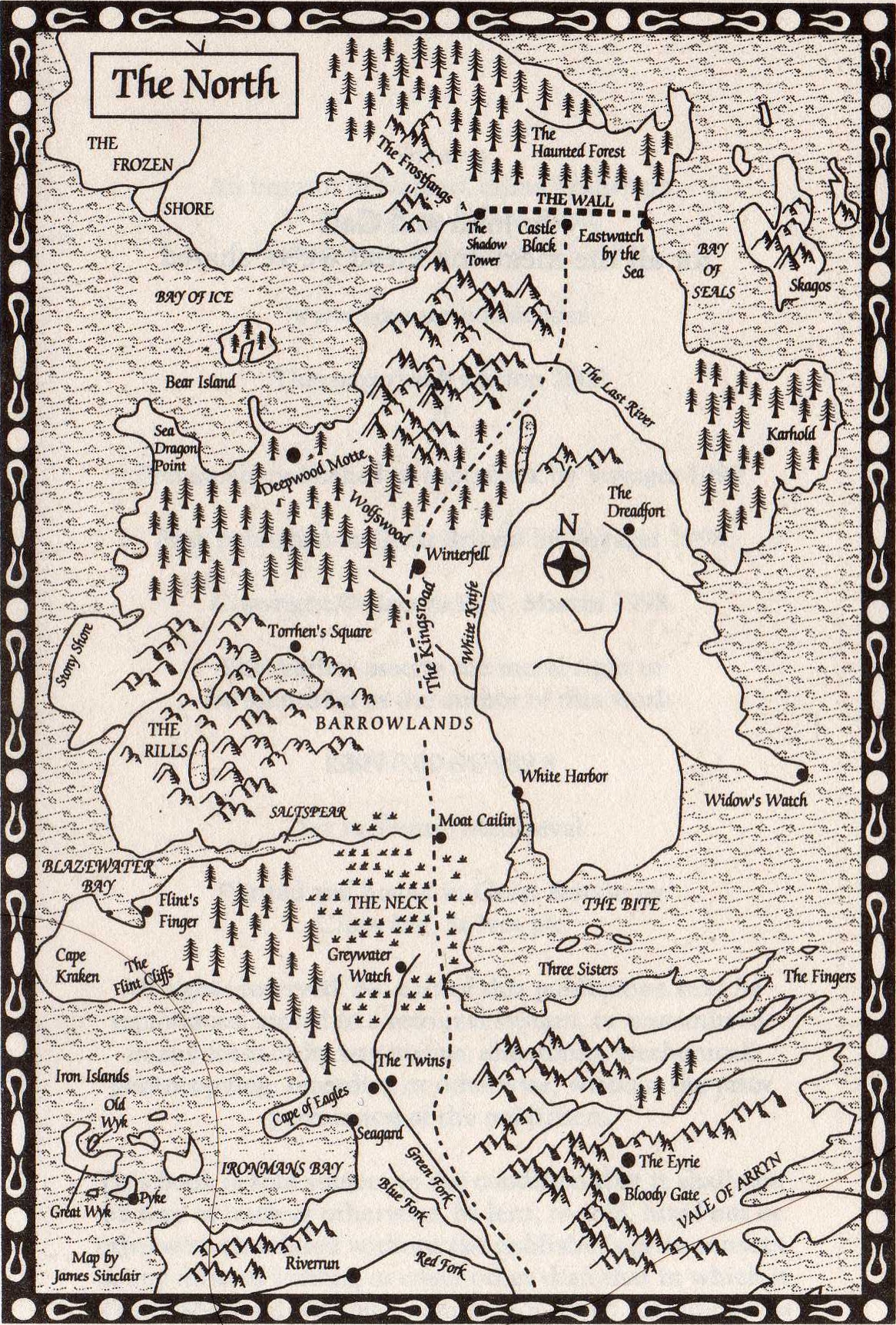

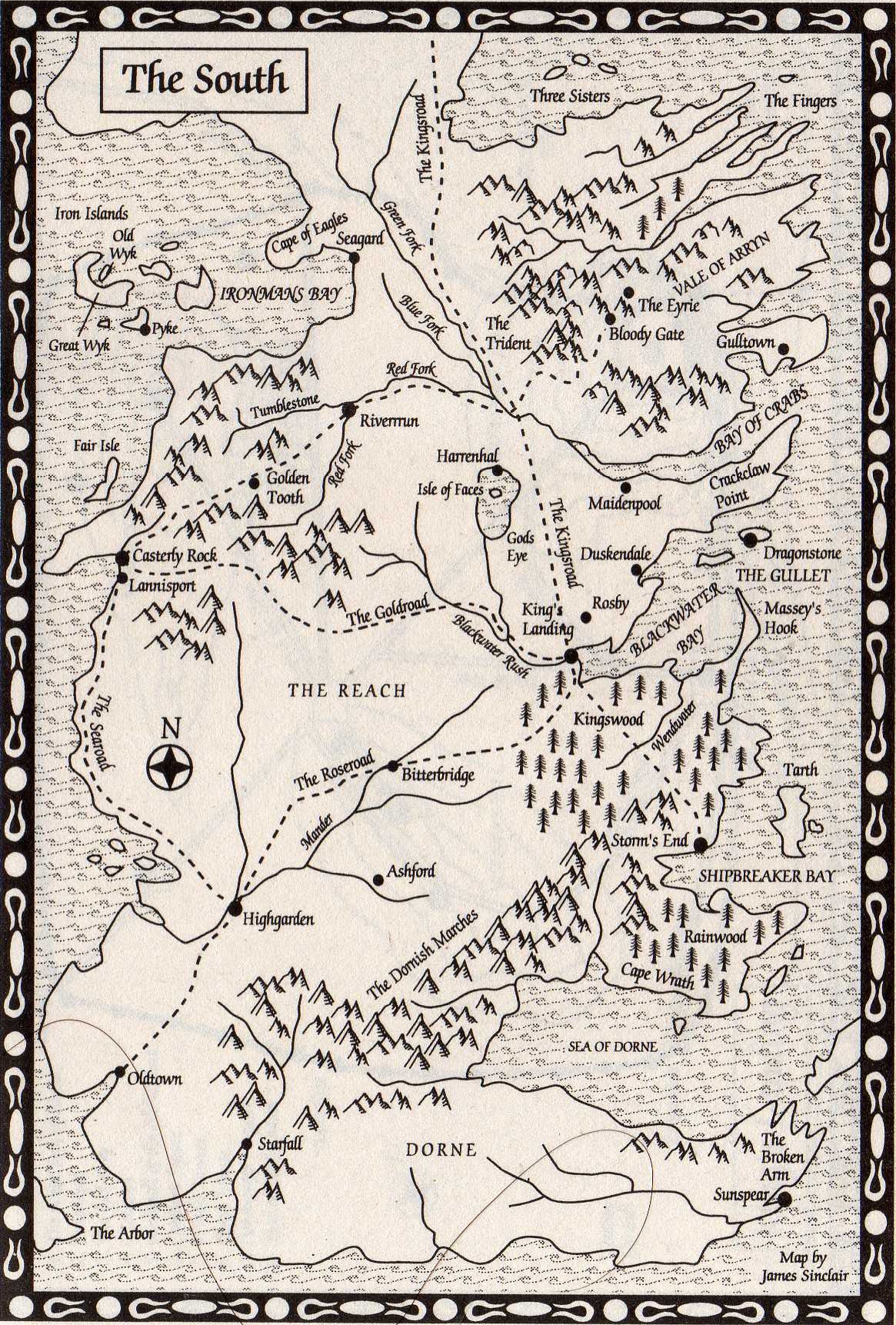

5. It has a map. But unlike most science fiction, this map is always important, and actually helpful. Brilliant and fun.

6. I question whether this is sensational. The sensational aspects are big plot points, and important to the story and the characters. So, yes, it is sensational in twincest and pushing young boys out of windows. But I don't believe that it is sensational simply to be sensational or edgy or unique. I think it's trying to be realistic, important, and not clichéd. So is its sensationalism a fault or not? On one hand, the density of sensational situations is too low for me to say that it is faulty, but it's also too high for me to say that it is not. However, for every sensational plot point, there are reverberations felt throughout the rest of the novels. I mean, the twincest is still affecting characters at the end of Book 5 in very significant ways. So whether it is faulty or not, he effectively uses the sensational plot points to drive the characters and story throughout.This is good work by Mr. Martin, and I think it is effective.

7. Like in the Count of Monte Cristo, something happens in every chapter that will echo into further chapters. Nothing is forgotten—which leads to fanboy-argumentative levels of complexity. Sure, some chapters are more important than others, but all have importance. There are no dead chapters.

8. Martin's writing is often a good mix of showing and telling. But he sometimes tends to redundancy here: sometimes the telling is after the showing, which means that the telling is supported by the showing or the showing is explained by the telling. But it feels like he's sometimes insulting the reader's intelligence by redundancy.

9. He tries to make every character sympathetic, but ends up making each unsympathetic. I actually like this. It lets the reader decide which characters are bad or good, a trust which softens the blow of insulting over-explanation. This is very effective.

10. Without direct foreshadowing, he foreshadows well. One character is obsessed with knights and marrying, and she ends up often interacting with knights and getting married once and almost married twice. However, it doesn't quite work out like she wanted it to. Another character is working towards a clash with a couple of the other groups of characters, which I fully understand is coming, but I do not know how or when it will happen. This indirect foreshadowing is done well, effectively drawing me through the story to find the closure that I know is coming.

11. The pacing pulls me along–each chapter ends on a bit of a cliffhanger. It drives the fine line between resolution and mystery enough to keep me going. I want to keep reading and see how the story from this chapter ends, which might be continued after an interlude of two or three more chapters, but by the time I'm done with the next chapter, I want to see how the story from that chapter ends, and the next one too. I think the length of the chapters helps him thread this line. In Book 1, each chapter is about half an hour, and in later books they are about 45 minutes each.

12. Despite his unimaginative word choices, his descriptions are good because he makes what he describes interesting. The list of knights in the hand's tourney is interesting—the sigils and armors and various body types of knights are varied and informative about their personalities, families, and homeland cultures. Though they're all Westerosi, there are differences between Westerosi of different places, and these types of descriptions really help flesh out the world. And he describes interesting characteristics of them in uninteresting ways. One man's sword is lit on fire before the melee, but it's sort of just burning there, not really described remarkably.

13. Like the Count of Monte Cristo, Martin breaks the narrative up with storytelling interludes. They break up the complex drama of the main story in little chunks of straightforward storytelling like old Nan's stories, or Meera's stories, or the stories of Ygritte. These are all welcome interludes that provide context and back story and history, but also breathing space and a break from the overarching complexity. Most are interesting and well done.

14. Contrasting the almost insulting over explanation of basic things, the reader is trusted with more information than some characters at times—why Bran fell, the death of Rickon and Bran, the twincest. This leads to a few "don't go in there!" moments, but it happens so rarely that it does not get old or seem like a cheap trick. Maybe this is a lesson to draw from it—some cheap tricks please the reader and, used sparingly, can feel like good storytelling or writing. This applies both two extra information and sensational plot points. Back to the Count of Monte Cristo, the mystery of who is who while the count is disguised also does this well.

15. Like with the female characters, I think variety is key to the whole series. The various male characters, different families, and varied plot points, experiences, and revelations spread throughout keep things interesting and readable. This is very effective for a long, complex novel series like this.

16. I like how each character's chapter can almost stand on its own—though Danerys more than most. However, they're so interconnected that they work much better together. [This relates back to the chapter structure outlined in point number 1.] Daenerys story acts as an ongoing example of those interludes I was talking about in point 13: through the first three books, her story is an interesting respite from the complexity of the Westerosi intrigues.

17. The slow pacing makes a book feel no less exciting or important. Like the Iliad, this is ponderous, narrow in scope, and full of importance—rather than fast, full of broad brush strokes, and lacking anything of import to think about. With the first book, it felt like this was the interesting, important bit of a much larger tale—like when Achilles kills Paris. Now, after all five books, I still feel like this is paced well, important, and interesting. The slow pace helps keep the complexity comprehensible, the variety of characters keeps the plot moving because when one is asleep another is doing something interesting, and the slowness encourages me to pay close attention to each part. In short, the pacing fits the setting, the plot, and the complexity. This works well.

18. The setting is believable—but even more than that, it's tangible. He creates a world and cultures from recognizable parts and pieces. Westeros is essentially the British isles, with Alaska tacked onto the top—land bridge and all—and both the Sinai Peninsula and Italy tacked onto the bottom. Europe is gone, and in its place across the English channel is now the Russian steppes and some major island countries from the Mediterranean. The Crows' Wall is Hadrian's Wall. The people are relatable too: they eat garlic and cows and other foods that we know today. It's inspired by the War of the Roses. The examples go on and on. This takes the world beyond believable to tangible, understandable, and effective.

19. Death lacks teeth. By the time of the Red Wedding, so many characters have died and come back to life that I'm not certain any of those killed in the Red Wedding are really dead—and not all of them are. Bran, Rickon, Aria, the three convicts in that cart, the lightning lord, the Crows who come back as wights, et cetera. These resurrections steal some of the drama and import from death. But death lacking teeth also helps build the world – so many of these characters face death on a daily basis as their job, or as the result of their desires, that to treat every single death as the massive plot point that the book is centered around would be unfair. Death is commonplace in the book because it is commonplace in Westeros.

[Added 8/31/15:

19. One other thing Martin does well is to forgo describing nights as lonely: describing times, places, or tableaux by the perspective of the point of view character on it. Rather, he factually states, "the day was gray," then allows the events, actions, and interior interactions of that day and the characters to color the whole in the reader's mind. Like in the beautiful, lengthy passage quoted in point two above, he simply describes the facts and therefore shows the scene with such specificity that he sets the mood without ever stating it. Cat is lonely in that passage, and anxious, and he does not have to spell that out explicitly, so he doesn't.]

This is about all five of the books in the Song of Ice and Fire series:

1. A Game of Thrones

2. A Clash of Kings

3. A Storm of Swords

4. A Feast for Crows

5. A Dance with Dragons

Because they are a continuous story and series, and they are so similar, I have chosen to talk about them as a whole instead of five separate books.

1. I find a distinction between a good writer who chooses words well and varies sentence structures interestingly, and a good storyteller—a writer who paces himself well, constructs the story in a clever way, and does not let a big story point become forgotten. Martin is the latter, not the former. For instance, the twincest is a big plot point, but it is never forgotten and never unimportant—and not in a sensational way, or not in a wholly sensational way. It is not a cheap, egotistical writer's trick, "Look at me! I will tackle even incest between twins! How courageous I am!" Rather, it is a major plot point and a fulcrum for the entire story. But the absolute best thing that George RR Martin does is his structure of sequential chapters from different characters' points of view. I have not seen this before in writing, so let me explain exactly what this is: in Chapter 28, Cat comes back from hearing that Tyrion probably attempted to murder her son, and ends up finding Tyrion on the road, so she kidnaps him; Chapter 29 is a royal tournament, told from the point of view of Cat's daughter; Chapter 30 concludes the royal tournament from Ned's point of view, and continues the thread of Ned's investigation; then Chapter 31 returns us to Cat and Tyrion, this time, however, the chapter is from Tyrion's point of view, with maybe two weeks to a month of time elapsed after he was kidnapped—there was as much time between his kidnapping and Chapter 31 as time spent in Chapters 29 and 30, which dealt with other story arcs. This is how the entire series is written. Every single chapter. This is brilliant and well done. I do not think I've come across somebody else who builds their chapters this way, and it's incredibly effective. This structure fits and maybe even encourages the complexity of the story. As a writer, I wonder at how much time Mr. Martin spends making sure that he has his facts straight, his chapters sequential, and his lore correct? This is complex stuff and he pulls it off. I would say 90% of that success is because of the fantastic chapter structure—he realized that with his complex plot, he would need this straightforward chapter system to keep everything legible.

2. On the other hand, the writing is not great. It communicates, and at times characters have their own voices, but on the whole its unremarkable. The writing begins in Book 1 as merely OK, then gets progressively better until the end of Book 1—but it never gets great except for these four paragraphs, which I think are stunning and beautifully written:

“Raid him here,” he said, pointing. “A few hundred men, no more. Tully banners. When he comes after you, we will be waiting”—his finger moved an inch to the left—“here.”I think this section is good writing. It is strong, describing something physical as "a hush", which describes the atmosphere that physical thing creates. But it's not as trite as the typical use of this tactic: "a painful-looking sword"—blech. Martin lists well: lists of characters at an event, tournament entrants, and lists like the one above—a small list to focus in on an event. This one repeats "here": describing it first as a future plan, then as a location, then as a relationship, then as an action. Using one word four times in four different ways was an effective way to build the tension and describe the emotions and perspective of the main character, while still describing the setting. Books 2 and 3 are a little less interesting to me for their writing than the last quarter of Book 1. The writing quality seems to go slowly downward, but this could easily be explained by the two year publishing schedule—Book 2 came out two years after Book 1, and Book 3 two years after that. Books 4 and 5 are mostly the same quality as the last quarter of Book 1 in terms of the writing, but there are some parts that are worse. In all five books published so far, nothing matches the beauty of that passage above from Book 1. However, at the end of reading all five, I remember two points were the writing was particularly bad. Perhaps once every 20 chapters or so I come across to phrase that makes me laugh aloud, and these two are the worst: at one point the phrase "man staff" describes a character's erect penis; and in describing a morning he writes, "The day was gray, overcast." These are both ridiculous. The second shows his tendency to insult the reader by over-explaining things as if they were idiots. But, so far this series is 4,273 pages, and there is going to be some ridiculous stuff in all that space. I am truly surprised that there is not more ridiculous writing, and I am also surprised that there is not more poetic beauty.

Here was a hush in the night, moonlight and shadows, a thick carpet of dead leaves underfoot, densely wooded ridges sloping gently down to the streambed, the underbrush thinning as the ground fell away.

Here was her son on his stallion, glancing back at her one last time and lifting his sword in salute.

Here was the call of Maege Mormont’s warhorn, a long low blast that rolled down the valley from the east, to tell them that the last of Jaime’s riders had entered the trap.

And Grey Wind threw back his head and howled.

3. The female characters are strong, well written, and believable without pandering to a single sense of "femininity". This is achieved through having multiple female characters—Sansa is a demure dreamer, Cat is a dutiful realist, Lysa is a protective paranoid, Arya is a free spirit—the females are as varied as the males, and as important. I heard somewhere that he wrote the females by just writing characters, and their gender was almost incidental after that. I don't know if that's true or not. But, to me, it seems like they are all women, through and through—though maybe that's because of the varied spectrum of female characters presented.

4. A major complaint about the series is a lack of a moral, or driving central theme. I don't think that's fair. Partway through Book 3 I wrote my notebook, "There are consequences. I think this is an important distinction: the gods do not appear powerless, though not all powerful either, but there are consequences to gaining their favors or boons or help. Satisfying a desire requires sacrifice—acquiring a desire requires prioritization, sacrifice, skull sweat, self examination, open eyes, planning, and maybe some money." After five books, I do think this is the central theme: you can't shake your past and you have to sacrifice on the altar of the future. One character searches for truth and ends up executed because the truth concerns those who could execute him, and his past complicated matters. Cat looks for the hand behind the attempted assassination, but her past history seduces her into believing lies, and in her desire to satisfy her curiosity she sacrifices the realm on the altar of the future. Every story arc, every character, every plot point comes back to the necessity of sacrifice. Sometimes the consequences are foreseen, and sometimes they are not.

5. It has a map. But unlike most science fiction, this map is always important, and actually helpful. Brilliant and fun.

6. I question whether this is sensational. The sensational aspects are big plot points, and important to the story and the characters. So, yes, it is sensational in twincest and pushing young boys out of windows. But I don't believe that it is sensational simply to be sensational or edgy or unique. I think it's trying to be realistic, important, and not clichéd. So is its sensationalism a fault or not? On one hand, the density of sensational situations is too low for me to say that it is faulty, but it's also too high for me to say that it is not. However, for every sensational plot point, there are reverberations felt throughout the rest of the novels. I mean, the twincest is still affecting characters at the end of Book 5 in very significant ways. So whether it is faulty or not, he effectively uses the sensational plot points to drive the characters and story throughout.This is good work by Mr. Martin, and I think it is effective.

7. Like in the Count of Monte Cristo, something happens in every chapter that will echo into further chapters. Nothing is forgotten—which leads to fanboy-argumentative levels of complexity. Sure, some chapters are more important than others, but all have importance. There are no dead chapters.

8. Martin's writing is often a good mix of showing and telling. But he sometimes tends to redundancy here: sometimes the telling is after the showing, which means that the telling is supported by the showing or the showing is explained by the telling. But it feels like he's sometimes insulting the reader's intelligence by redundancy.

9. He tries to make every character sympathetic, but ends up making each unsympathetic. I actually like this. It lets the reader decide which characters are bad or good, a trust which softens the blow of insulting over-explanation. This is very effective.

10. Without direct foreshadowing, he foreshadows well. One character is obsessed with knights and marrying, and she ends up often interacting with knights and getting married once and almost married twice. However, it doesn't quite work out like she wanted it to. Another character is working towards a clash with a couple of the other groups of characters, which I fully understand is coming, but I do not know how or when it will happen. This indirect foreshadowing is done well, effectively drawing me through the story to find the closure that I know is coming.

11. The pacing pulls me along–each chapter ends on a bit of a cliffhanger. It drives the fine line between resolution and mystery enough to keep me going. I want to keep reading and see how the story from this chapter ends, which might be continued after an interlude of two or three more chapters, but by the time I'm done with the next chapter, I want to see how the story from that chapter ends, and the next one too. I think the length of the chapters helps him thread this line. In Book 1, each chapter is about half an hour, and in later books they are about 45 minutes each.

12. Despite his unimaginative word choices, his descriptions are good because he makes what he describes interesting. The list of knights in the hand's tourney is interesting—the sigils and armors and various body types of knights are varied and informative about their personalities, families, and homeland cultures. Though they're all Westerosi, there are differences between Westerosi of different places, and these types of descriptions really help flesh out the world. And he describes interesting characteristics of them in uninteresting ways. One man's sword is lit on fire before the melee, but it's sort of just burning there, not really described remarkably.

13. Like the Count of Monte Cristo, Martin breaks the narrative up with storytelling interludes. They break up the complex drama of the main story in little chunks of straightforward storytelling like old Nan's stories, or Meera's stories, or the stories of Ygritte. These are all welcome interludes that provide context and back story and history, but also breathing space and a break from the overarching complexity. Most are interesting and well done.

14. Contrasting the almost insulting over explanation of basic things, the reader is trusted with more information than some characters at times—why Bran fell, the death of Rickon and Bran, the twincest. This leads to a few "don't go in there!" moments, but it happens so rarely that it does not get old or seem like a cheap trick. Maybe this is a lesson to draw from it—some cheap tricks please the reader and, used sparingly, can feel like good storytelling or writing. This applies both two extra information and sensational plot points. Back to the Count of Monte Cristo, the mystery of who is who while the count is disguised also does this well.

15. Like with the female characters, I think variety is key to the whole series. The various male characters, different families, and varied plot points, experiences, and revelations spread throughout keep things interesting and readable. This is very effective for a long, complex novel series like this.

16. I like how each character's chapter can almost stand on its own—though Danerys more than most. However, they're so interconnected that they work much better together. [This relates back to the chapter structure outlined in point number 1.] Daenerys story acts as an ongoing example of those interludes I was talking about in point 13: through the first three books, her story is an interesting respite from the complexity of the Westerosi intrigues.

17. The slow pacing makes a book feel no less exciting or important. Like the Iliad, this is ponderous, narrow in scope, and full of importance—rather than fast, full of broad brush strokes, and lacking anything of import to think about. With the first book, it felt like this was the interesting, important bit of a much larger tale—like when Achilles kills Paris. Now, after all five books, I still feel like this is paced well, important, and interesting. The slow pace helps keep the complexity comprehensible, the variety of characters keeps the plot moving because when one is asleep another is doing something interesting, and the slowness encourages me to pay close attention to each part. In short, the pacing fits the setting, the plot, and the complexity. This works well.

18. The setting is believable—but even more than that, it's tangible. He creates a world and cultures from recognizable parts and pieces. Westeros is essentially the British isles, with Alaska tacked onto the top—land bridge and all—and both the Sinai Peninsula and Italy tacked onto the bottom. Europe is gone, and in its place across the English channel is now the Russian steppes and some major island countries from the Mediterranean. The Crows' Wall is Hadrian's Wall. The people are relatable too: they eat garlic and cows and other foods that we know today. It's inspired by the War of the Roses. The examples go on and on. This takes the world beyond believable to tangible, understandable, and effective.

19. Death lacks teeth. By the time of the Red Wedding, so many characters have died and come back to life that I'm not certain any of those killed in the Red Wedding are really dead—and not all of them are. Bran, Rickon, Aria, the three convicts in that cart, the lightning lord, the Crows who come back as wights, et cetera. These resurrections steal some of the drama and import from death. But death lacking teeth also helps build the world – so many of these characters face death on a daily basis as their job, or as the result of their desires, that to treat every single death as the massive plot point that the book is centered around would be unfair. Death is commonplace in the book because it is commonplace in Westeros.

[Added 8/31/15:

19. One other thing Martin does well is to forgo describing nights as lonely: describing times, places, or tableaux by the perspective of the point of view character on it. Rather, he factually states, "the day was gray," then allows the events, actions, and interior interactions of that day and the characters to color the whole in the reader's mind. Like in the beautiful, lengthy passage quoted in point two above, he simply describes the facts and therefore shows the scene with such specificity that he sets the mood without ever stating it. Cat is lonely in that passage, and anxious, and he does not have to spell that out explicitly, so he doesn't.]

Labels:

1996,

1998,

2000,

2005,

2011,

Fantasy,

George RR Martin,

Locus Award

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_von_Anhalt.jpg/438px-Codex_Manesse_(Herzog)_von_Anhalt.jpg)

%2C_f.40_-_BL_Cotton_MS_Nero_D_IX.jpg/648px-Jean_de_Saintr%C3%A9_jousts_with_Enguerrant_-_The_Romance_of_Jean_de_Saintr%C3%A9_(c.1470)%2C_f.40_-_BL_Cotton_MS_Nero_D_IX.jpg)