Showing posts with label Arthur Clarke. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Arthur Clarke. Show all posts

04 August, 2015

Childhood's End by Arthur Clarke

1. I do not think the Clarke is bad at creating characters, as opposed to Heinlein; just that Clarke's characters only serve the story, so they are abandoned after their usefulness. Like here, the head of the U.N. is a very good character—an honest portrayal of the aging statesman on the brink of retirement. And he fades out once the story moves into the future 50 years. The story is not about him. Or really any other character. Clarke's stories are typically about something other than a character or situation. Here it is about mankind's curiosity and capacity to change. Though the Supervisor lasts the whole novel, it is not focused on him and therefore is not really about him. Clarke writes like a good historian and anthropologist—think Thor Heyerdahl's Kon-Tiki or Giles Milton's Samurai William—rather than a more traditional storyteller. The characters serve the story, not the other way around as it often seems like Heinlein does.

2. Let me modify one thing: I think the theme of the story is creativity—which is the combination of curiosity and capacity to adapt, in a sense. At the end, when mankind is adapted to something beyond recognition and our ability to fully fathom, they return to creativity and their interest in pushing past their comfort zones in an attempt to find their place, to come of age, to end their childhood. Further, each section of the novel can be said to have creativity as a central theme: Stormgren is creative when he catches a glimpse of Karellen, an action which is the culmination of that section; Jan's creativity leads him to not only discover the Overlord homeworld, but to figure out a way to get there and achieve his goals; New Athens is all about creativity, a sort of artist's colony attempting to create creativity in the absence of struggle and strife; and at the end, the Overlords study the children in an effort to recreate their actions. The novel is centered on creativity. It examines what typically leads both towards and away from creativity. It places creativity as a basic human characteristic, maybe even a need.

3. The basic philosophical conclusion is that mankind's end must echo man's end: the life of one man who dies of old age is book ended by feebleness and rapid change—we both start out and end up crawling and unable to support ourselves by ourselves. Here Clarke theorizes that mankind's evolutionary path must be the same—we begin relying upon the earth, our mother, for everything, which mostly includes our material wants; and we end up relying upon our father, a "great consciousness", and his winged minions to guide us towards acceptance of our material mortality. This is an interesting idea for mental gymnastics that Clarke further expands in his later book 2001: A Space Odyssey. However, in 2001, the second frailty applies to only one man and it is more of a second birth than a final death. Here it applies to all mankind, and because the perspective is on Jan and the Overlords at the end, there's more emphasis on the final death of the material form, not what the humans become.

4. The paranormal activities within the book are interesting and help lend a mystery deeper than the plot's mystery of the Overlords. It is an element of few novels, yet Clarke makes it interesting, engaging, and keeps it from being sensational. It seems courageous to take on something as a key minor theme that every reader will have an opinion on. I thought it was done well.

5. The human race is lulled into lethargy by a Golden Age that destroys their quality creative outputs. This is a difficult assumption to follow. When faced with the sheer mystery of the Overlords, I have a hard time believing that every human would fold up their hand and step back from the table of progress and creativity. I don't buy it. Clarke's deus ex machina explaining away is simply that a culture's change in 50 years can be great—inconceivable even. This is shallow. It's only inconceivable because Clarke did not show it to the readers.

6. This episodic novel lacks a frame narrative, but does not need one. It still works because it is tied tightly together with the overarching theme of creativity, which acts in place of a frame narrative. The religions of the world all fall once the creativity of interpreting historical mysteries and context evaporates. Once the mystery of "can we travel in space?" is revealed—yes, we can—the creative search for how ceases. Once the necessity of creative living through strife and struggle is removed, artistic output ceases to be relevant or quality. As I noted above, this is a hard pill to swallow, but it is the theme that holds the episodes together and gives the whole novel legibility.

7. Some of the episodes shift scope: Clarke uses a macro angle on the Ouija game and the Greggson's life in New Athens, but often shifts to a wide angle perspective of humanity as a whole. The novel switches from details to broad brush strokes and then back again. This also is similar to 2001. And it works for me because both the detailed examinations and broad overviews are centered upon that central theme. I find this tactic interesting, but at times difficult. I think he almost always pulls it off here without jarring the reader too badly—after all, a new chapter is not just following the last chapter; or, chapter breaks signal those scope changes adequately—but it is not something I feel like I want to try in my own writing just now, because of the danger of losing the reader and my preference for exploring characters. It is like he keeps changing the context and the characters, just like a historian who examines a character central to the historical thread he is following, then the context surrounding that character, then that character again, then the context again, etc. This specifically reminds me of both Nathaniel's Nutmeg and Samurai William by Giles Milton.

8. I do not want to seem to say that this book is bad, because it isn't: I enjoyed it immensely. But I enjoyed 2001 more, and that treads a lot of similar ground: what makes us human, human evolution, a great consciousness meeting humanity, and the creative and curious drive to explore, know, and progress. This novel does step out on its own in alien invasion, religion, and social engineering; where 2001 expands into AI, space travel, and prehistory. I enjoyed both novels, but experienced some fatigue reading them back to back due to their similarities. And I enjoyed 2001 more.

Labels:

1953,

Arthur Clarke,

Science Fiction

03 August, 2015

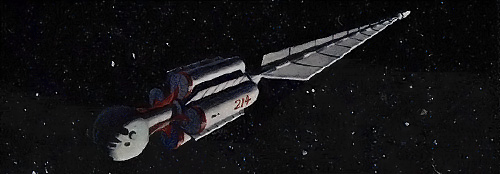

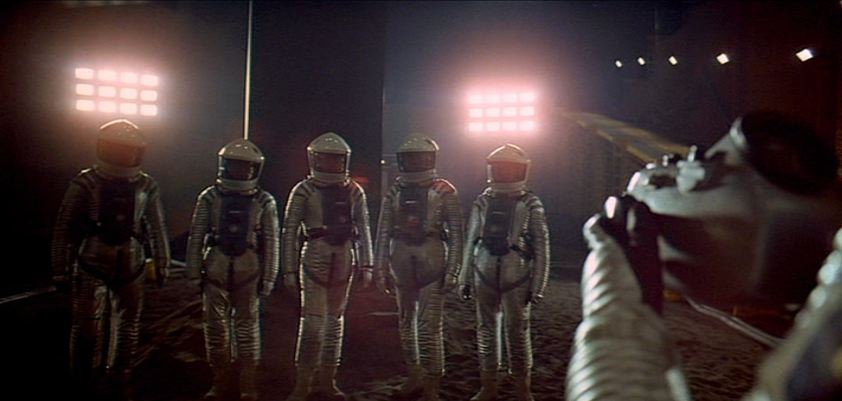

2001: A Space Odyssey by Arthur Clarke

1. One thing that I really enjoy about Clarke, both here and in Rendezvous with Rama, is his ability to give information in a way that laymen can understand and enjoy. This might be my bias of loving layman's physics, but here it interests me. This could be some pretty dry stuff—explaining slingshoting spaceships—but it works here. He finds that line between too much information boring the reader, and just enough information told in an interesting way to make learning enjoyable.

2. While he does this with physics, the detailed description of life aboard the spaceship is a bit boring. It is an incredible feat of imagination—even for Clarke, who is known as a fantastic predictor of the future—but it seems to drag on, much like the days must drag on for the two astronauts who are awake.

3. HAL is a great character. He ends up being so human in his panic, his difficulty to maintain a lie, and his return to childlike behavior—all while still being unavoidably computer. He believes that all people must be like him because he is the only existence he knows. This is a powerful character, and an effective emotional tragedy.

4. HAL's fault—the conflict of lying about the mission to the astronauts, then concluding that these instructions to lie must indicate that the astronauts are nonessential—is a beautiful moral metaphor, and convincing examination of future technology. Like much science fiction, Clarke examines a current thread in culture—AI and space travel here—and pushes it to a logical extreme to show both potential benefits and pitfalls. The basic premise that shakes out is the truism that humans know not what they do. By not knowing how HAL will develop, they know not what their creation will do. Here Clarke could have gone the pulp route and made HAL a secret villain delighting in punishing and testing the meatbags. But instead I empathize with HAL. He is a well developed character. His flaws are part willful and part ignorance and part situational, much like mine tend to be once I fully glimpse them.

5. The scope of this book is fearless: tackling a timeline from pre-human to post-human. I think Clarke pulls it off, which is amazing. He is a confident, talented author biting off a huge chunk of material, and getting it to do exactly what he wants. And he does it well. This is an episodic novel without a frame narrative, but this structure actually works here because the thread is so important to each episode. Human evolution and change is that thread, and it is central to every part of the book. Even the opening pre-human part is the same narrative as the other parts. The echoes come back in situations so different from the original that they offer new insights and the theme rolls along, keeping it all together. This tactic of a central theme tying all of the episodes together would have helped Foundation, where the central eponymous element changed so drastically between episodes that the novel felt disjointed.

6. As to that first part, the pre-humans are described with an empathy that is touching. What we take for granted today, their great leaps of logic, are almost as astounding in the showing as they could be. I think merely telling about them would have lacked power, but there's just enough telling to ensure and confirm that the reader is on the same page with the author and characters.

7. Clarke's world building here is amazing. But most of his characters are merely good. In this way he's almost the opposite of Heinlein: whose characters are great, but whose world building is not as perfect as they are. I am not saying that Clarke's characters are bad, they're just not as perfected as his world building.

8. At the end, I want more. Star Child blowing up the satellite is such an enigmatic and powerful act that I'm looking forward to seeing how this post human goes, and what it does. The contrast between it and humanity is so great that I'm interested to see if it becomes a god, and what humanity does next. The temptation is obviously there narratively for Star Child to assume divinity. But if there's one thing that I know about Clarke, it is that he foils whatever I predict he's going to do, then shows why what he came up with is more logical and correct.

9. Clarke's writing is not amazing, but it is good. His teaching moments are very good—and I think it is a special, valuable talent to be good at making orbital mechanics interesting. But he does have moments of brilliance here, the high point being: "Sorry to interrupt the festivities, Dave, but I think we have a problem." This is just one example, but it is so great! Overall, this is above average writing with moments of brilliance.

10. Another place where Clarke bites off more than the average author can chew is in the nearness of his future—this is not thousands of years hence; it is something he will probably see in his own lifetime. [He did live through 2001 and the intro to the audiobook that I listened to was really enjoyable, reflecting on what he got right and wrong, the way the book was written, and its influence.] It is courageous to try this. And although there are some clear differences between his work and how the future actually shook out—we have no AI, the human body requires a lot more exercise in space than he anticipated, we have yet to attempt artificial gravity in space, we have sent no manned missions farther than the Moon, etc.—he pulls the whole off well enough that it does not feel dated to me. Reading space travel stories by HG Wells or Jules Verne is difficult today, because all of the disbelief that must be suspended to buy into the narrative. Not so here. This is easy. 2001 has become alternate history since it was published, but it still works well.

Labels:

1968,

Arthur Clarke,

Science Fiction,

Space Odyssey

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)