27 July, 2016

Gate of Ivrel by CJ Cherryh

1. The beginning of this novel is difficult to get through: so self-indulgent in that density of unknown names in the intro info dump—fifteen or sixteen made-up fantasy names in a page and a half. Your reader has not been given the chance to know or care yet! This is the worst intro info dump I’ve read. If I wasn’t curious about Cherryh’s first novel because I've fallen in love with some of her others, I would not have read any more than a couple of pages.

2. A part of that intro info dump describes the background for the world, and another the background for the story. If you must have separate backgrounds for both, maybe they need to change. So, it’s a science fiction world that has collapsed back into fantasy—though here that familiar ubi sunt motif is portrayed as paranoia or lust for power rather than curiosity or awe or frustration. This split is not Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light, but more like William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, which has just a single sentence showing the post-nuclear war context. And that’s interesting in the abstract. But in the specifics of this book, with one science fiction character hiding everything from many fantasy characters, it comes off confused—the context of these time-warping gates being built and people failing them may be interesting, but the story of a quest to close one of them is restricted from her intro's premise. She didn’t use that work she put into world building, so the novel comes off discongruous.

3. The writing is bad. There is a tendency in fantasy to overdo the cadence and wording of the work: “Lo, thusly spaketh your Lorde” type stuff. Cherryh here isn’t that bad, but it’s bad going that direction. The word “hi” is used throughout in situations like “she rode hi the mountain Irvel”, or “he put his helm hi his head.” Ugh. Horrid.

4. The story entertains well though. It’s a fantasy quest and chase where everything keeps going wrong: the main character accidentally kills his brother and gets banished right off the bat, then he is forced to work with his religion’s devil and gets Stockholm Syndrome, he gets poisoned, he gets captured, he is encouraged to suicide, he narrowly misses being sucked out of his dimension, he is shot at more times than I can count, his body is almost stolen from him by a soul that uses other’s bodies to continue living, he loses the key to closing the gate, he almost breaks his oath, and he’s almost left behind at the end. It’s not a pleasant quest for him. Remarkably, Cherryh doesn’t use deus ex machinas to free him from all these situations—his freedom and safety comes about from as many diverse influences as his dangers do. And, like Gawain and the Green Knight, dealing with the cold and snow in armor is almost more of an antagonist than any character.

5. The world is built through showing over time. Despite the intro info dump, it’s a growing familiarity as these names are used in the story itself. And, as implied above, the parts of the world she does include in her story are important and have effects, which really helps it all stick together well. Nothing is forgotten, except the science fiction undertones laid out in the intro.

6. So, in all, not my favorite Cherryh novel by a long, long shot. It’s bad. The theme deals with identity and community, and the story hits at some early strengths that Cherryh will build on later—also, she does begin to leave out unimportant things in a way that hints at her later, tight voice. But to see the progression she went through from here, in 1976, to Downbelow Station in 1981 is staggering. And it’s hard work and practice that got her there: she published something like 14 books over that time period and had a few of them written before her first publication here.

Labels:

1976,

CJ Cherryh,

Fantasy,

Morgaine Saga,

Science Fiction

20 July, 2016

Serpent's Reach by CJ Cherryh

1. This 1980, early Cherryh novel exhibits moments of brilliance alongside boilerplate science fiction standards. For instance, the world Cherryh builds is rigorous and fascinating. It’s far-future in the Alliance and the eponymous region of the galaxy is composed of a number of stars and planets. The planets contain humans called betas, who are normal to us today; azi, third class human clones; and also the aristocratic Kontrin humans—essentially immortal as one has never died of natural causes and they live for more than seven hundred years. There are many different families and splinter-families of the assassination-oriented Kontrin. The beta humans' culture is supported by the spending of the aristocrats, and subject to Kontrin whims. The betas are split up into cultures by worlds and stations. The azi serve both of the other human classes as well as the aliens, hive creatures called Majat who have their own class system: the central mother brain, warriors, drones, workers, and azi. The Majat are split into four factions, or hives. This complex culture is fascinating throughout. Part of what makes the book’s world seem believable is that these complexities are not thrown away—Cherryh uses them in order to drive the plot and affect the characters. Keep this in mind: introducing complexity is useless and distracting unless that complexity feels necessary to the story. It’s like designing a board game: cut out all the rules possible, focusing on the decisions that make the game fun. Cherryh does this well here: almost every part of the worldbuilding is used in the story and is important.

2. But the story, nature of the aliens, and characters come off as fairly standard science fiction fare.

—The novel’s adventurous revenge story has enough violence to put up a high body-count, but in the end it’s just another adventure story. She uses the action hooks to hang introspective and interesting moments off of, but I can’t decide whether it wants to be action or discussion. The first half tries to be discussion, but essentially just sets up the world in order to get to the lengthy second half which is almost entirely action. But, like most adventure novels, it starts with a bang, goes into the setup, then ends with a lengthy sequence of bangs.

—The aliens come off like so many other hive-mind aliens: Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, Joseph Haldeman’s The Forever War, Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men, Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep, and Arthur Clarke’s Childhood’s End, to name a few of many. I don’t believe these hive aliens are unique enough to stand out from the crowd. The hive competition is interesting, but not enough to carry the novel. The Majat don’t feel as alien as the Calibans in Forty Thousand in Gehenna—Majat feel like azi or slaves the way that Raen uses them.

—The characters are also fairly commonplace. Raen, the main character, is bent on revenge, but it’s not tearing her apart—she’s sure of herself and her goals and her growing perception. She is not as wrinkled as the eponymous Count of Monte Cristo. The psychology almost gets interesting, but doesn’t quite reach enough depth—preferring instead the action of the story to the applicability of psychological discussion.

3. There are three characters that do shine: Pol, Moth, and Jim. Pol is a jokester, an activist—the disillusioned adult poking holes in the fabric of cultural reality to expose hypocrisy and idiocy. But he doesn’t get enough time on-screen to really shine. Moth is “entropy personified” as Raen calls her at one point. But she knows more than the other characters and her inaction is her choice to let others act to bring about her ends. Jim is initially an azi—more slave-like here than in other novels—but he gets pushed off balance by Raen, who attempts to convert him from his tape-training to more general uses. He ends up taking entertainment as deep-tape, allowing her Kontrin entertainment to modify his basic personality. He almost dies from it, but he comes out of it more Kontrin than azi. These three characters all get enough discussion to make them interesting, but more space should have been spent on them to make the whole novel more interesting. Jim is not explained enough, Pol doesn’t get to act often enough, and Moth resisting the conspirators could be fleshed out better.

—The most interesting thing in the novel is the Raen-Pol relationship: enmity, admiration, and understanding fill their fascinating encounters. Raen is doing what Pol wishes he could, but can’t tell him because he wouldn’t keep his mouth shut. Still, they are wary of each other—their secrecy keeps them from understanding the other fully and working together closely. But once Pol realizes, or is forced into a position of vulnerability in front of Raen’s enemies, he helps her and eventually pulls off the coup de grace that allows Raen’s plan to succeed.

4. Cherryh’s fantastic, distinctive, closely focused, third-person voice is coming into its own here. There are flashes of surprise that show why she writes this way. Where did Pol’s gun come from? I don’t need to know, but he suddenly has one and uses it perfectly for Raen's plans. My surprise at him standing and shooting matches Jim’s at that moment. What’s so tacky about the house’s entrance? Rather than spending pages explaining the interior design of the culture to show the reader why it’s tacky, Raen just judges it tacky and moves on, allowing that judgment—and the judgment of the bedroom as superb—to question her pre-conceived notions of the normal humans. In other words, Cherryh tells rather than shows in this case, but still allows the telling to change the characters. Cherryh is exploring her chosen voice here, not yet comfortable, but also not throwing it away without its flashes of brilliance.

5. The theme here is that man is more alien than aliens. Variety and believed-familiarity breeds blind-spots that take Raen by surprise. Like the bedroom/foyer dichotomy, like Moth, like Pol, like Jim, like the farm-family, like the azi, she is consistently surprised by those around her and only through accepting accurate reality is she able to succeed. The aliens are little more than a plot device here, but Raen’s growing realization of reality is the real focus of the novel.

6. Many have noted that there are continuity errors with dates given, the azi, and Alliance-azi relations. But these don’t matter to me. Cherryh, early in her career, was still thinking through these things and wasn’t going to explain everything in her first try. It could be some alternate Alliance-Union universe—it could be something weirder—but it’s a story and she did her best. She changed her mind later, and I’m more than okay with that: I support a writer changing their mind.

7. In all, this is a fine book. It’s really slow to start out as the world-building requires so much to allow the complexity. But it pays off with the second half—an exciting adventure through that world she just built, taking it apart piece by piece and changing it massively. This novel hints at what Cherryh would go on to write—deep, psychological character studies in rigorously complex cultures with plenty of political conspiracy—but isn’t quite there yet. I enjoyed the adventure of it all, and contemplating the conclusions of the culture she created, but I wanted more insight into the characters and more screen time for the most interesting ones. I'm not convinced the end is what needed to happen, but it's believable.

Labels:

1980,

Alliance-Union Series,

CJ Cherryh,

Science Fiction

15 July, 2016

The Sharing Knife: Beguilement and Legacy by Lois McMaster Bujold

0. I treat these two books as one because that was how they were written: Lois McMaster Bujold wrote them as one story, then split them for size and publishing reasons. And it’s obvious in the reading: the first ends with the paramours riding away from their wedding, towards Dag’s family, with no sense of things being tied up—except with Fawn’s family. The second ends with almost everything tied up except for three questions. Also, the writing is indistinguishable between the two. Therefore, one set of notes. Well, as it turns out, only one note.

1. I consistently approach books and films with as much of a blank slate as possible—watch no trailers, never read the back of the book, look at no reviews. I appreciate surprise and exploration above many things in life, and I find going into books blind more informative than taking pre-conceptions with me. This novel starts out as fantasy, building a complex and engaging world about ancient evils that periodically awaken to steal the life-force of things around them, growing stronger and stronger until killed by a magic knife that has captured the death of a human. This life force is called ground and certain people can sense it like gravity, or hearing. McMaster Bujold does a brilliant job introducing the reader to this concept simply, by spreading the explanation out over a couple of chapters.

—She begins by building characters: initially Fawn Bluefield, who is a Farmer, a term for those who cannot sense ground. Beginning with what is familiar to the reader—Fawn is like us. This helps the fantastic elements find their place in the reader’s mind by having something pre-existing to relate them to. This reference point and her questioning persona help build the world through dialogue. I find it works well.

—Then she brings in the fantastic elements by introducing the other main character, Dag Redwing. He is a Lakewalker, somebody who can sense ground, and a patroller who patrols for malices—those ancient evils periodically waking up. He and his patrol encounter evidence of a malice’s slaves and start hunting the malice, showing plenty of glimpses of ground-sense in action, but no real strong explanation—whetting the reader’s tongue.

—Then Fawn gets captured by some of those slaves and Dag ends up rescuing her. Their time together allows her questioning to get explanations out of Dag in dialogue, telling the reader more than they could infer from the actions already shown. This is where the heavy-lifting of the fantastic elements of the world-building occur. And it’s an effective tactic, using dialogue to tell after actions have shown.

—Then together they kill the malice and the story would typically end here with the heroic deed done. But McMaster Bujold continues writing, talking a lot about what comes after the heroic deed. And I am terribly interested, hoping that she explains the world more fully in what is essentially the paperwork and party after the heroes act heroically.

—But what comes out of left field is the sex. There is a romance set up already, but this is real bodice-buster stuff using words like "stroking". The rest of the novel is a fantasy quest tale with one more malice kill tied into a lot of romance and sex. Having set up such an interesting and deep world—with its own mythology, customs, and history—McMaster Bujold does give the reader more of that world, but it is also a romance novel with explicit sex scenes. The novel reads eighty five percent like a great fantasy novel, and fifteen percent like a romance novel.

—If I had known it was a mashup of romance and fantasy, I would have been waiting for the romance and felt the other shoe drop at its arriving. Not knowing, I was surprised, and that's the novel not standing on its own. Other than Jane Austen, I haven’t read any romance, but I don’t really enjoy the romance here. How it compares to most other romance I don't know, but it’s not as enjoyable to me as Austen. The way the opening was written, I didn’t expect the romance and wasn’t looking for it. Therefore, it felt like a short story—a really good short story ending after the malice kill—that she then decided to tack a novel onto. It felt disjointed: after the malice kill, she has to reintroduce the reader to the second part, which takes up the rest of these two books, which deals with the romance and the families of the two paramours. I don’t find this restart to be smoothly accomplished: she paid so much attention to world building in the first part, that the second part switches tracks too awkwardly. This is my main complaint with the novel: not that it’s poor romance, but that it starts out as fantasy-adventure, dips into post-adventure fantasy, then becomes romance-fantasy. I love Pixar films because they set up the premise right at the start—toys have their own lives when we’re out of the room—and if you buy that premise, everything else follows logically. This book sets up a premise, stretches it into an examination of what happens after the heroic act, then switches premises to romance. Like Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, I found it blundering and discongruous. The rest of the novel, at least the eighty-five percent that adheres to the original premise, is good fantasy. That fifteen percent is always ill-fitting though.

2. And that’s my main take-away from this novel. She set up the world and story so well, then added other things in too late that didn’t inform or add anything to the characters or novel other than fan service sex scenes. If that’s what somebody wants, this is the novel for them. I mean, I finished reading it. I will certainly read more by McMaster Bujold because I enjoyed that eighty-five percent so much. But I wont be reading more in this series because it’s split down the middle and can’t decide what it wants to be: there’s not enough romance to be a romance novel, and too much romance to be a fantasy novel.

1. I consistently approach books and films with as much of a blank slate as possible—watch no trailers, never read the back of the book, look at no reviews. I appreciate surprise and exploration above many things in life, and I find going into books blind more informative than taking pre-conceptions with me. This novel starts out as fantasy, building a complex and engaging world about ancient evils that periodically awaken to steal the life-force of things around them, growing stronger and stronger until killed by a magic knife that has captured the death of a human. This life force is called ground and certain people can sense it like gravity, or hearing. McMaster Bujold does a brilliant job introducing the reader to this concept simply, by spreading the explanation out over a couple of chapters.

—She begins by building characters: initially Fawn Bluefield, who is a Farmer, a term for those who cannot sense ground. Beginning with what is familiar to the reader—Fawn is like us. This helps the fantastic elements find their place in the reader’s mind by having something pre-existing to relate them to. This reference point and her questioning persona help build the world through dialogue. I find it works well.

—Then she brings in the fantastic elements by introducing the other main character, Dag Redwing. He is a Lakewalker, somebody who can sense ground, and a patroller who patrols for malices—those ancient evils periodically waking up. He and his patrol encounter evidence of a malice’s slaves and start hunting the malice, showing plenty of glimpses of ground-sense in action, but no real strong explanation—whetting the reader’s tongue.

—Then Fawn gets captured by some of those slaves and Dag ends up rescuing her. Their time together allows her questioning to get explanations out of Dag in dialogue, telling the reader more than they could infer from the actions already shown. This is where the heavy-lifting of the fantastic elements of the world-building occur. And it’s an effective tactic, using dialogue to tell after actions have shown.

—Then together they kill the malice and the story would typically end here with the heroic deed done. But McMaster Bujold continues writing, talking a lot about what comes after the heroic deed. And I am terribly interested, hoping that she explains the world more fully in what is essentially the paperwork and party after the heroes act heroically.

—But what comes out of left field is the sex. There is a romance set up already, but this is real bodice-buster stuff using words like "stroking". The rest of the novel is a fantasy quest tale with one more malice kill tied into a lot of romance and sex. Having set up such an interesting and deep world—with its own mythology, customs, and history—McMaster Bujold does give the reader more of that world, but it is also a romance novel with explicit sex scenes. The novel reads eighty five percent like a great fantasy novel, and fifteen percent like a romance novel.

—If I had known it was a mashup of romance and fantasy, I would have been waiting for the romance and felt the other shoe drop at its arriving. Not knowing, I was surprised, and that's the novel not standing on its own. Other than Jane Austen, I haven’t read any romance, but I don’t really enjoy the romance here. How it compares to most other romance I don't know, but it’s not as enjoyable to me as Austen. The way the opening was written, I didn’t expect the romance and wasn’t looking for it. Therefore, it felt like a short story—a really good short story ending after the malice kill—that she then decided to tack a novel onto. It felt disjointed: after the malice kill, she has to reintroduce the reader to the second part, which takes up the rest of these two books, which deals with the romance and the families of the two paramours. I don’t find this restart to be smoothly accomplished: she paid so much attention to world building in the first part, that the second part switches tracks too awkwardly. This is my main complaint with the novel: not that it’s poor romance, but that it starts out as fantasy-adventure, dips into post-adventure fantasy, then becomes romance-fantasy. I love Pixar films because they set up the premise right at the start—toys have their own lives when we’re out of the room—and if you buy that premise, everything else follows logically. This book sets up a premise, stretches it into an examination of what happens after the heroic act, then switches premises to romance. Like Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, I found it blundering and discongruous. The rest of the novel, at least the eighty-five percent that adheres to the original premise, is good fantasy. That fifteen percent is always ill-fitting though.

2. And that’s my main take-away from this novel. She set up the world and story so well, then added other things in too late that didn’t inform or add anything to the characters or novel other than fan service sex scenes. If that’s what somebody wants, this is the novel for them. I mean, I finished reading it. I will certainly read more by McMaster Bujold because I enjoyed that eighty-five percent so much. But I wont be reading more in this series because it’s split down the middle and can’t decide what it wants to be: there’s not enough romance to be a romance novel, and too much romance to be a fantasy novel.

Labels:

2006,

2007,

Fantasy,

Lois McMaster Bujold,

Romance

14 July, 2016

Forty Thousand in Gehenna by CJ Cherryh

1. Unlike Cherryh’s typical character focus, this novel discusses a situation over a long time-span of 305 years. The situation is a new colony on a habitable nut little understood planet. The book starts with it being founded, flourishing, and collapsing. Then being rediscovered, studied, and collapsing again. Then, between the on-screen scenes, being rebuilt and thriving. In Cherryh's universe, the science fiction theme clearly test-runs theories of first contact, and studies how azi and humans react to collapse. In this way, I think this is the most space operatic novel I’ve read by Cherryh, though her whole Alliance-Union universe tends towards this sub-genre as all the books are so interlocked.

From Section D: Mission Report by Dr. Cina Kendrick

Intelligence is not, as indicated above, a scientific term. [...]

Two considerations must be made. First, that an organism’s behaviors may be survival-positive in one environment and not in another, and second that its perceptive apparatus, its input devices, may be efficient for one environment but not for another. The quality imprecisely described as intelligence is commonly understood to describe the generalization of an organism, ie, its capacity to adapt by the use of analogy to a variety of situations and environments.

On the contrary, even the concept of analog is anthropocentric. Logic is another anthropocentric imprecision, the attempt to impose an order (binary, for instance, or sequential) on observations which themselves have been filtered through imprecise perceptive organs.

The only claim which may be made for generalization as a desirable trait is that it seems to permit survival in a multitude of environments. The same may be said of generalization as part of the definition of intelligence, particularly when intelligence is used as a criterion of the inherent value of an organism or its right to life or territory when faced with human intrusion. Generalization permits migration in the face of encroachment; and it permit one species to encroach on another, which adds another dimension to natural selection. But when extended to intrusion not over another mountain ridge within the same planetary ecology and the same genetic heritage, but instead to intrusion of one genetic heritage upon another across the boundaries of hitherto uncrossable space, this value judgment loses some credibility.

2. However, this novel isn’t all situational—well-developed characters still fill the pages. But it’s character by mindset more than specific individuals. Characters who take a non-interventionist policy oppose those who take a more helpful role, and both camps contain exploitative characters. These ideas are spread through the novel: from Union’s first contact with the Calibans, to Alliance's first contact with the Gehennans, to Gehenna's first contact with the Unioners, to Farsider’s first contact with a Gehennan.

—First, the Union colonists’ ignorance leads them to assume that the Calibans are stupid. This allows catastrophic destruction of the Union mission—both in the slow trickle of children away from their control, and the base being physically undermined and collapsing.

—Second, the Alliance comes in slow and indecisive—non-interventionist in word, but not so much in deed. Their base is way too close for comfort and their observation post changes what they observe. Their confidence in their space-based surveillance is similarly poorly placed—they can see the whole, but no details and are just as ignorant as to the meaning of the whole. Like when McGee heals Elai’s leg, it’s half-assed through indecision: in her own misplaced confidence and self-conflicted desire to save a child’s life, she doesn’t search for or get out the near-fatal bone-spur. This fumble sets her mission back fifteen years, until Elai’s mother dies. The Alliance's indecision as a whole leads to war, death, and the destruction of half the Gehennan culture. Finally, both the Alliance and Gehennans decide to educate and put their pride aside enough to be educated, and that seems the right track. (I read McGee’s pattern as a clear step in this direction.)

—Third, the Union comes in hungry for knowledge and offering trade. Elai rightly recognizes that the Union needs nothing from her, and calls their bluff. This is entirely the wrong foot to start out on for the Union: the wary reaction of the Calibans—leading to the Unioners further fear-based reaction—illustrates this. The Union is still ignorant to the point of not knowing how to engage their potential teacher, and this ultimately loses them their final influence over the colony.

—Fourth, the Farsiders appear to find the Gehennan curious, but the knowledge they do have—from videos and reports—allows even the rough docksiders to avoid an incident. Similarly, the Gehennan and Caliban pair chosen for the visit are appropriate for the high number of strangers they expect to run into.

—McGee, Genley, Elai, Pia, Jin, Jin Younger, Jin Elder, and Scar are the main characters, but the mindsets clearly steal the show from the people. These are well constructed, interesting characters; but they are not as important to the novel as the mindsets.

—And I find this discussion of the mindsets of First Contact to be the theme of the novel. First Contact here is a metaphor for the other. In our day-to-day lives we are consistently pushed outside of our normal comfort zones to deal with unfamiliar people, opinions, situations, etc. There are two ways this typically goes: fear or understanding. Education and embracing the unknown—quite literally in McGee’s case—leads to an inclusion that grows knowledge and culture. Fear leads to death. That’s Cherryh’s point and she makes it well throughout the novel by focusing on the mindsets—though she doesn’t lose sight of the individual characters in a way that shows how small acts have large consequences. Humanity will survive because it has generalization, but that's not always a good thing when the situation or environment pushes us, even on an easy, habitable, fruitful planet like Gehenna.

3. Cherryh set herself a hard task in the various writing tactics of this novel. She includes memos and portions of scientific papers to show the affect actions have on the whole.

I propose that, instead of arguing old theories which have considerable cultural content, we consider this possibility: that humanity develops a multiplicity of answers to the environment, and that if there must be a system of polarities to explain the structure around which these answers are organized, that the polarity does not in and of itself involve gender, but the relative success of the population in curbing those individuals with the tendency to coerce their neighbors. Some cultures solve this problem. Some do not, and fall into a pattern which exalts this tendency and elevates it, again by the principle that survivors and rulers write the histories, to the guiding virtue of the culture. It is not that the Cloud River culture is unnatural. It is fully natural.Another aspect is researchers’ notes:

Is even childhood one of our illusions? Or is this forced adulthood what’s been done to us out here?And memos also fill the pages, at least one going through draft after draft showing McGee’s mindset and final words, exposing much about her character and her dissatisfaction with the powers over her. Further, the Union, Alliance, Styxside, and Cloud River cultures all have their own voices, and the latter two communicate also via hand gestures and drawing patterns. It’s a plethora of writing tactics, causing Cherryh to switch gears consistently in a way that keeps the writing all fresh and exciting. It’s not all one voice, though Cherryh’s typical tightly focused voice is on display fully.

Us. Humans. They are still human; their genes say so. But how much do genes tell us and how much is in our culture, that precious package we brought from old Earth?

What will we become?

Or what have they already begun to be?

They look like us. But this researcher is losing perspective.

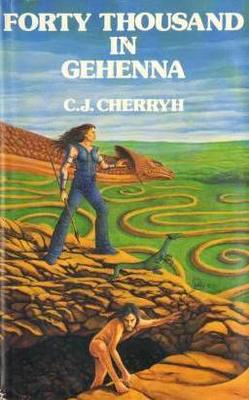

4. Many of these memos and papers take the place of actions and interior monologue in a way that makes the novel seem a little slow. There’s a lot that happens over these three hundred and five years, but most of the novel is people reacting to those changes and settling in as best they can. The action is usually fast—a couple of pages—and decisive, leaving the bulk of the novel to unraveling the meaning of those actions and what they signify. This isn’t necessarily a negative as I was enthralled throughout, but covers that show a human riding on a dragon-like creature mislead and that first edition cover (at the top) is the most informative as to what the novels feels like. Not sedentary, but also not rollicking, despite what the following cover wants you to believe:

5. This is a good novel. I wanted a bit more action and a bit more psychological depth—Jin Elder and McGee are really the only two who have any depth. But then, maybe that is me projecting on the novel too much of Cherryh’s other works, kind of like how Union and Alliance project on the Gehennans too much of their empirical data. I like seeing Cherryh trying a new method of storytelling with the time span that disallows her usual deep individual psychology, but I think her strengths primarily rest in the other way she writes. That’s not to say this isn’t a wonderful novel, because I really enjoyed it. It’s certainly better than other situational novels I’ve read, like The Plague by Albert Camus.

Labels:

1983,

Alliance-Union Series,

CJ Cherryh,

Science Fiction

08 July, 2016

Finity's End by CJ Cherryh

1. What a tour de force! This novel is Cherryh sticking to what she does best—not ignoring any experimentation, but slightly modifying what she does well: an opening to introduce the characters, set the context, and get the story rolling in a quick, engaging way; deep introspection throughout for Fletcher, a slightly damaged main character trying to come to terms with a new situation; a supporting cast of actual characters who have their own philosophical insights, instead of being set-piece-characters; illuminating a central act through spaced out near-repetition of it, adding more to the reader's understanding each time; believable change within the characters that could only come from what happened within the novel; word choices and sentence structures modifying to fit the factions within the story; pacing that allows both rumination and action; and that wonderful, tightly focused voice that never allows the author to spoon feed the reader. In the rest of the Company Wars novels, Cherryh explores and focuses on some of these things, and here all that work pays off in a novel that clearly demonstrates a refinement and perfection of her skills. I just have one small complaint.

2. That ending is too pat, too tied up, too tidy. Sure, the Hisa stick is no deus ex machina—it has significant other importance to Fletcher, James Robert Sr, James Robert Jr, Jeremy, Satin, Elene Quen, and the whole of the ship Finity’s End throughout the novel. It’s final importance to the Alliance is being unveiled slowly as Fletcher matures and thinks his way through his past—so it’s no deus ex machina. But when Fletcher decides to search for the stick at the importers, I feel this is going to be a typical Cherryh ending: part tragedy, part triumph, all interesting puzzle to roll over in my mind for a few days after. In the end, it feels like the cost didn’t measure up to the victory gained. Sure, Fletcher being put in his place regarding Jeremy is a big change, but because he’s already gone through that—with his mother, Pell Station, Patch, Melody, Satin and the whole downer culture, Downbelow Station, Bianca, the rest of the crew, and his last foster family—this latest break isn’t a surprise, it’s a repetition. Things are different now in the sense that Fletcher is accepting the ship, with all its faults, with Jeremy’s actions, and more importantly with his own actions. But just explaining the ending in a minute to somebody makes the novel seem like a happy-ending too pat for any interesting thoughts. Thinking about it more and more, I realize that it isn’t, but it does come off that way. Cherryh could have better illuminated the cost to Fletcher at the end, and I think that would have helped. As the novel slowly pieces itself together in my mind after the fact, as events come into hindsight focus, the whole makes a lot of sense and the actual cost becomes clear, which is why this is only a small complaint.

3. Otherwise, this novel is perfect. I love it. I wish I would have written this novel. The most intriguing bit is, of course, Fletcher, the main character. This novel is Fletcher learning to look past himself and recognize reality. Even the time-dilation of the spacers points this out prominently, when Fletcher initially mistakes Jeremy for a twelve year-old. But what’s so intriguing here is that this realization of reality goes through a lot of wrong steps before Fletcher finally finds something solid to stand on. He wants to find a family, then he gets disgusted with humans and wants to work with Hisa, then he wants to change policy so he dreams of being administrator to Downbelow, etc, etc, until he realizes that he cannot stand on his own first impressions and ends up apologizing, trying to make right, and doing something good for the ship. He’s not fixed at the end, but he is on the right track finally. (In this sense, the end makes perfect sense: he finally breaks enough to be useful to others, and he is quite useful to the whole Alliance.) It’s not optimism, his desire to bring the stick before the Alliance, but it is the best in a set of bad possible decisions, and he goes about it the right way, for once. This growth, this acceptance of reality and his need to work within it, is the theme of the book, and the triumphal ending drives home Cherryh’s point successfully.

4. JR is a fascinating character. In many ways he is the foil to Fletcher within the novel. Where Fletcher is distrustful and destructive, JR is comfortable and committed. JR has it all figured out, and what he doesn’t have figured, he knows where to find. However, Fletcher’s arrival and the ship going off of a war footing, shoves him out of his comfort zone and he cannot quite find the right tactics to deal with this new aspect to his reality. Where Fletcher has trouble dealing with reality at all, JR has a hard time integrating new pieces into it, and tells himself that his caution is a virtue. He retreats to his current reality, hiding from the new of Fletcher. However, by the end, he too has grown, has changed, has taken a few steps of his own, on his own initiative, and come off fine for it. These two characters are, unlike other Cherryh novels, the only two main characters in the book. But the book doesn’t lack for that because by focusing herself down to just these two, it allows Cherryh to get deeper into their psychologies and philosophies in a worthwhile way.

5. This novel feels like the philosophical point the rest of the Company Wars novels are trying to make. All the discussions about the past come to a head here, refined. The pacing and depth are spectacular. The writing is satisfyingly varied in word choices and sentence structure. What more can I say? This is perfect.

02 July, 2016

Tripoint by CJ Cherryh

1. My question here is this: does this book stand on its own? I don’t know. But this question will guide these notes.

2. What a wonderful novel. This book carries on the quality of Hellburner: a well paced story that doesn’t forget to stop and take a walk in the woods; engaging, damaged characters overcoming themselves as much as others; there is no such thing as a free lunch -esque interpersonal relationships and politics. But this novel definitely is its own thing: Cherryh engages that broad political scope that affects her macro focus on the characters in a more direct, more explanatory way. In Hellburner, she focuses clearly on trying to get the ship to work. In this twenty years revenge tale, the context is everything that has occurred over the last twenty or so years at Mariner, Viking, Pell, Tripoint, the Rim Stations, Sol, and on the two ships that are the focus of the novel: Sprite and Corinthian. The characters respond to the big political shifts, but being free merchanters, they know more and discuss more of the broader politics. This wide angle perspective and narrow character focus creates an intimidatingly intriguing novel and it reminds me of The Fifth Season by NK Jemisin in that way. But I’m not sure that somebody who hasn’t already gathered what Tripoint is from Cherryh’s other works, should read it. The intricate relationships and political maneuverings within the Alliance play a most important role here, but they are alluded to in other novels that I have read, allowing me a familiarity that may have helped me understand more than the novel gave. I’m not sure, but it’s a possibility that reading at least Downbelow Station first really helped make this novel superb for me.

3. The writing here is superb, some of the best I’ve read from Cherryh. She manages to communicate things the reader must imagine, but in a way that makes them still strange. For instance, a portion of Tom’s story involves the spacer-sin of staying awake during jump.

They say you don’t come back sane, you leave a part of yourself out there in the chaos of the parallel universe. Well, among the Mazianni, it’s a mark of a good navigator to grow used to that place, to learn to read the sights and sounds of it, to literally feel themselves passing by masses, to feel starships around them.This military necessity creates a sort of mysticism in certain circles, and Tom runs into Capella, described perfectly as a “lend-lease navigator” from the Mazianni fleet—which has fractured into at least three parts: The Fleet, Mazianni, and Signy. Capella is from The Fleet and initiates Tom into this activity of staying awake when all else are tranked out—initially from pure lust and later for emergency purposes. Her guidance allows him to remain sane. But more profoundly, because Cherryh’s voice doesn’t allow a ton of description until a character sees something new or in a new way, it allows wonderful and beautiful descriptions:

He lay still—he thought he was lying down, Saby lying near him, but whether it was light or dark didn't seem relevant to his eyes. He saw, somehow, or something like. The brain kept shifting things around or the walls truly ran in streams of color. Things just were. Couldn't see Capella, then shivered at a strangeness as her hand met his body.But these are framed stunningly—Cherryh just drops them on the reader from nowhere: a lengthy, semi-erotic dream sequence describing jump to a tranked out human is strange, then gets stranger when he wakes up and the reader just doesn’t know until later what happened:

Pale, then. Capella's blonde, brazen flash and try-me attitude, Capella standing there with her bare arms resting through bars he recalled he wasn't dreaming, with the bracelet of stars evident on her wrist. It wasn't the freedom of the docks he was in, he was in a box he couldn't get out of, and an exposure that let the whole ship come and stare at him if they liked.It’s fractured and seeming nonsensical. But by the end of the book, the reader has a pretty good idea what being in jump would be like—unfathomable as a whole, but bits of it parsable.

Capella gave him an I-don't-give-a-damn rake of the eyes, leaned there, enigma like the fatal holocards. Her hands were death and life together, the serpent and the equation that cracked the light barrier, the bracelet no honest spacer wore…

Colors washed to right and left of him, red and blue and into infrareds and ultraviolets, a tunnel at the black peripheries of his vision. He daren't come any further. Christian wasn't his friend. This woman wasn't. This dream was destructive. He could make it go away.

He felt the loneliness, and the cold. Then… just felt/ smelled/saw the colors a while. And vast, terrifying silence. He tried to move, then. He couldn't feel things. Couldn't tell up from down. He leaned into space, flinched back toward solid limits, and thought he was falling.It’s these sentences—short, declarative—that jump around and don’t seem to fit together, but sometimes they do in a rambling, rolling way: the sound of it reminds him of music from another time, but he can’t remember time. But then Cherryh also allows phrases to shift out of place: something looks green but tastes purple and orange, and smells blue. These experimental steps are phenomenal, and her description is astounding. She spends a lot of pages to do what she does with jump, and I loved every second of it.

Arms were there. Caught him. Hands showed him where level was.

—However, without the context of the other Merchanter novels setting up that aversion to not tranking for jump, I’m not sure this exposition of what that experience is like would actually fly. It’s maybe a third into the novel when Tom wakes up in a jump, and I feel like I wouldn’t have bought how insane some people go when that happens if I hadn’t read the others. It’s as if Cherryh is saying it’ll drive you crazy while showing a character or three who ends up coming through it alright. A bit of a contradiction.

4. There are a few main characters: Tom, Marie, Austin, Christian, and Capella. And each of them gets portions of chapters devoted to them in a way that tells the story from multiple points of view. It is Tom’s story, but it’s told from the perspective of others as well as his own, and it grows out of others’ stories—kind of like how our lives do. This challenges the reader to make up their own mind about the story and characters within, instead of spoon-feading the reader opinions to hold about characters. I like this tactic when George RR Martin does it, and I like it here.

5. On one hand this is a revenge story and the theme is Marie’s revenge for rape. But the real theme is Tom's coming of age, his realization of reality. The book takes place twenty years after the rape and Tom’s still trying to find a place, a group of people he can belong to. And he finds it in the unlikeliest place: on the ship of the rapist, his father. But it’s not because Austin is his dad, but because Saby and Tink befriend him, accept him, support him in a way his mother and her ship never did. Yes, he hates his father. But he wants a new start and it's really the only place, the only choice he has. This theme is all tied up with ignorance and codes of conduct in a way that really strikes home for me. And Marie's rape echoes where each echo adds some to the reader's understanding and keeps drawing one deeper. This theme is applicable and understandable to somebody who never has read any other Cherryh.

6. I love this book, a lot. On the one hand the theme allows the book to stand on its own while the political context is probably a neutral influence—it may or may not help to have read her other novels. Taking the jump awake almost certainly relies upon the other novels to set the stage, but could potentially be grasped by a new reader—which I think is unlikely. So, on the whole, the book probably doesn’t require one to have read her other work, but it certainly doesn’t hurt. And for that, despite this being a real treat of a novel, it doesn’t quite stand on its own. But that’s the nature of a long series like this—seven novels in this Merchanter or Company Wars branch of Cherryh’s broader Alliance-Union universe. So I love this novel, a lot, but can’t quite recommend it as easily as Downbelow Station.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_3.jpg/640px-Komodo_dragon_(Varanus_komodoensis)_3.jpg)