30 January, 2016

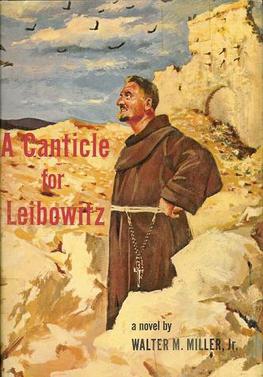

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M Miller Jr.

1. This novel consists of three novellas loosely related in plot. This structure works well for Miller because each novella contains a central plot: the revelatory discoveries of Francis, the birth of a Renaissance, and the second apocalypse. Aside from these three plots, each novella also engages a fairly significant secondary discussion: savagery and culture, human curiosity and creativity, and a religious perception of incompatibility between science and religion. Each novella is around 100 pages, and these discussions and plots fill the space well in each portion: they never lag in either action or reflection. They are held together by things that will be discussed in later points.

2. Further, the structure simply follows one major character and spends a couple of chapters with other characters—the same character through all three parts, the old Jew Lazarus; as well as the Thon, another monk in Texarkana whose name I forget, buzzards, sharks, and the fleeing monks. These short interludes from other characters’ points of view serve to build the world. This simple structure keeps everything tight and focused. Through these three main characters, the stories stay focused on the three discussions mentioned above, as well as the three plot points. Using a single character per portion contains the story and discussions. Okay, so we have three novellas, three plots, three major discussions, and three characters. Let’s move on from these catalogues of successful structural tactics to talk about how Miller integrated these three novellas into a novel.

3. These three novellas relate closely through sharing a theme, telling a continuing story with large time breaks between them, and using the location of the Abbey of Saint Leibowitz. Dang, that’s another catalogue of three. Sorry. We’ll take them in order. First, the theme of the novel explores knowledge, science, and religion. We initially see the Catholic church in relation to purposefully unintelligent tribes, as some start to see benefits to knowledge. We then see the church existing at the start of a Renaissance, giving over their knowledge to the secular intelligentsia. Finally, we see the ignored church struggling to find a place in the world of science. These three states of the church and surrounding culture illuminate Miller’s theme of the church’s influence on culture and vise-versa. A framing theme of cyclical history supports Miller’s reframing the history of the Catholic church’s influence on culture in this post-apocalyptic Catholic tale.

4. Second and third, the whole novel tells a continuing tale, staying with the monks and nuns of the order of Saint Leibowitz, and their ancient abbey. This mostly rigid focus makes a strong base for the reflection on themes and discussions. These reflections spin out to backstory, philosophy, and cultural criticism, but always come back to that base, always exists upon that base. This circling keeps the whole novel moving, while the base keeps it all legible and combined.

5. The writing is fine, here. Miller strikes a good balance between a wide vocabulary, Latin interludes, and concise language. His language is efficient and gets out of the way for the ideas and themes to really take center stage. This is a positive because the book is clearly driven by its ideas.

6. One problem is a pacing issue: Francis dies so suddenly in the first part that it disappoints, a bit. His death reinforces the savagery of that portion of the novel, making it a tragedy. But, my problem is this: to use such a sudden and final event to end the first portion just to reinforce the savagery of the time period seems cheap and hamfisted. Miller had already built a pretty savage world and I don’t need that reinforcement there. I much prefer the ten days of buildup given to the apocalypse in the third portion.

7. I enjoy this book to some extent. Miller certainly does a great job trying these three novellas together. But the theme seems a little overdrawn—by the end I’m a bit bored thinking about the Catholic church and its relation to culture. Miller attempts to keep me riveted through the three other discussions noted in point number one. And this is almost successful, but the moderate hamfistedness left me moderately disappointed. It’s a good book, but not great.

Labels:

1960,

Henry M Miller Jr,

Hugo Award,

Science Fiction

25 January, 2016

This Immortal (aka ...And Call Me Conrad) by Roger Zelazny

1. This book has a problem: it is referential to a fault. A lot of paragraphs draw parallels to a wide array of references—ancient Greek myth, contemporary 1960s culture, and pop cultural references timed between the ancients and the 1960s. These references are so thick that it easily loses the reader at times. But never for too long. Zelazny always shows what the references mean, rather than telling, yet the references are still too much. They bog the reader down with questions of what the references mean: there are simply too many of them to allow any reader to know all of them. This fault moderately reduces my enjoyment of the book.

2. The other problem is major and can be stated more simply: Zelazny is concise to a fault. The plot is threadbare and the wonderfully witty dialogue almost too fast. Things happen quickly with little or no set-up or rise in tension. This makes everything seem quick and perhaps unplanned. Of course, the last three events—the dead man, the hot spot, and the black beast—are foretold by Conrad’s son Jason. But Jason shows up out of nowhere, the cannibals show up suddenly, and the black beast appears and is beaten before it has any real impact on the story or characters. This fault massively reduces my enjoyment in the book. I wanted to really explore some of the plot points, exist in them for a time, and contemplate some of their ramifications. Instead, I’m left wondering what effect the hot spot had on Hasan; the black beast is a quick, simple battle and I’ve no idea as to its significance to the world at large; the pipe playing happens so fast with no real transition to allow me to properly place the characters. In other words, things happen so quickly I’m still a bit unsure what is dream and what is plot. There is a balance to grasp here, that Zelazny doesn’t: too slow and the reader gets bored, too quick and the reader gets lost, though between too quick and too slow exists a wide gray area of pacing that I enjoy. Zelazny moves too quickly and this book doesn’t hold me the way Lord of Light, Zelazny’s later book, did. This quickness also makes events seem like deus ex machina at times, which is a negative. If he adds something to the reader’s knowledge of the world, you can bet that within ten pages, that new element will come by to save the day.

3. Now that those two unpleasantnesses are dealt with, I can move on to why I enjoyed this book. First, the writing is superb. Zelazny strikes a perfect balance here between beautiful and efficient language that kept me engrossed and enjoying even the referential sentences I didn't understand at all. I loved Zelazny’s writing here, full of consonance and internal rhyme, but not over the top. He also uses a lot of analogy to say things. One example is that the two shots of the elephant gun at the end are likened to the thunderbolts of Zeus. This analogy wonderfully keeps the mood of myth and mystery, while being a worthwhile description of what actually occurred.

4. Second, the characters are engrossing and distinct. Though the book tends towards quickness, ending up more a novella than a novel, the characters are well developed mostly through dialogue, but also through sparse use of Conrad’s psychic power. Zelazny uses dialogue to build the characters, rather than extensive backstory or an omniscient narrator’s description. The book takes the form of Conrad looking back on these experiences, telling them to the reader from his point of view. This let’s Conrad’s exposition of the characters really focus on the dialogue and actions of the others.

5. Third is the plot—it’s both a post-apocalyptic tale and a post-contact story. This combination seems odd conceptually, but Zelazny ties them together enough that my imagination runs wild. Again, the quickness steals some of the satisfaction I should feel at these two tales being woven together well, but there is enough in there that I greatly enjoyed the plot and the implications for planet Earth.

6. The main character is Earth, not Conrad. That’s really the whole gist of the book—what happened to Earth, what it’s like in the book, and the potentials it's left with at the end. This ties into the theme of adaptation. I don’t mean that in the ecological sense too deeply—to me the theme centers around Conrad adapting his tactics to fulfil his goals, and modifying his goals as a necessity. For instance, in the past Hasan, Phil, and Conrad bombed islands and killed the alien invaders in an attempt to galvanize a return to Earth by ex-patriots. However, they both realize that will never work and change their tactics. Phil becomes the consummate socialite, helping to establish and preserve a reason for some to stay on Earth. Conrad becomes a governmental official, helping to distinguish Earth as a unique entity—Earth for Earth’s sake, with all the warts and boils inherent in it. They both have changed to continue attempting to accomplish their goals of making the world better for humans. Their goals also change by abandoning the naive hope to work against the aliens, realizing instead that alien power and influence necessitates working with them. This adaptation requires a realistic appraisal of the situation and some deep changes in the characters. But they end up being successful only by subduing their earlier impulses for bloodshed: they destroy their earlier efforts in order to create a new balance.

7. This book is a wonderful read, partly because it is so short. Any longer and the quickness with which it dispatches plot points would’ve been overly trivial. The characters are strong: Conrad is a superhuman anti-hero, as is Hasan; Earth is a vibrant and damaged, the damage adding to the diversity and vibrancy; George the single-minded scientist; Ellen the socialite flitterer; Red the neophyte of a past iteration of Conrad. What little plot there is grips the reader and provides abundant space for the reader to fill in the blanks and spin their imagination to fantastic places. It’s all a single chapter, start to finish, and Conrad follows the action pretty closely. A worthy read, but not great. This shared the Hugo for best novel in 1966 with Dune, which is a better novel to me. But for a novella, this book is fun—especially the writing; for that writing I will forgive a lot. The novella category was added to the Hugo awards in 1968.

Labels:

1965,

Hugo Award,

Roger Zelazny,

Science Fiction

18 January, 2016

The Wise Man's Fear by Patrick Rothfuss

The fiftieth posted set of notes on this blog.

For Isaac and Garrett.

1. So much sex. It felt like twenty percent of this novel was sex-scene. Three explanations spring to mind right off the bat: two pessimistic and probably wrong, one optimistic and probably right. First, perhaps Rothfuss was disappointed winning young adult literature awards for the last book, The Name of the Wind, and wanted to separate himself from that potential pigeon hole, so he added sex. Second, his audience grew four years since the last book, putting those young adults into puberty by now, and sex sells. These two pessimistic potential reasons are far from the simplest explanation though: it seems Kvothe is now 16, and sex is certainly a thing at that age. I believe this third reason, though there is still a lot of sex in this novel.

2. But Rothfuss writes the sex well: it lacks both sensationalism and stuffy moralizations. It’s not explicit, like George RR Martin is, but nor is it lightly implied and unconfirmed. He strikes a balance between the two that allows the sex to teach Kvothe much about himself, others, the world, history, the Fae, and morality. What I mean is that Rothfuss doesn’t moralize the sex, but through sex, Kvothe understands better how to treat other people and himself, how to do so morally—even in the differing morals of the different places and people he encounters. I want to say that he treats sex like he does magic and music, and mostly that’s true. It’s just that first sexual encounter with Felurian that potentially betrays that treatment. But even then, it’s treated like the first time Kvothe discovers his own music next to the pool in the forest, and his first sympathy in Ben’s cart. So yeah, the sex is treated like magic and music. It’s well done.

3. Rothfuss’ writing improves here: his sentence structures are slightly more complex, and he broadens the vocabulary he uses. This improvement is slight, but marked. It raises the quality from legible to readable—readable in the sense that I’m not constantly substituting words while reading it because I’m bored by his word choices, like I was in the first book. These minor changes increase the quality of the writing a lot. It’s a small change that makes the book much more enjoyable.

4. The improvement to the writing is necessary because this book is 1,000 pages long. If the writing hadn’t improved, this would’ve probably been a slog. One thousand pages is a long novel. Rothfuss uses 152 short chapters, averaging 6.54 pages per chapter. This is dangerous in that the short chapters break up the writing so much that it could feel like I’m constantly starting and stopping as a reader. By contrast, Martin uses long chapters to break up his long books: each is basically a short story. Here, each chapter is not short story: something happens in each chapter, something distinct, but it’s not quite as deep as a short story. Because Martin jumps around between characters in every chapter, he needs the longer chapters for supplementing his character building and making each chapter memorable so that when the book returns to that character a few chapters later, he doesn’t have to refresh the reader’s memory and slow down the story telling. Here Rothfuss sticks to Kvothe and keeps the story rolling, explaining even the travels between spaces in order to keep the focus on Kvothe’s story. It works for him with these short chapters.

5. Speaking of storytelling, Rothfuss is on fire here. Instead of a typical novel structure of one major crisis being built up, happening, then resolving, this is the story of Kvothe. He goes through many crises, resolves them, and then the novel stops. This isn’t a negative, because each portion of the book—college, Maer, bandit hunt, Fae, Adema, and college—are all self-contained novellas. In essence, this book is six novellas put together. Yet they’re all interconnected so closely that this novel works very well and the edges of each portion bleed into the next—most apparent at the end, when he returns to college and the story of his deeds in the other four portions catch up with him. This serial structure shows the novel's kinship to any series of short pulp fiction novellas. It could seem meandering if Kvothe didn't change from all of these experiences, but because he does, the novel is tight and a quick read.

6. As a character, Rothfuss shows and tells Kvothe well. The writing strikes a fine balance between showing Kvothe’s actions and reactions, and explaining Kvothe. One of Rothfuss’ tactics is borrowed from pulp fiction: he tells the action without letting the reader know the why, then explains it later. For instance, when Kvothe kills the troupe, it’s unclear to the reader what he thinks, why he’s angry. It feels very out of character for Kvothe and the novel, which is more violent than the first, but not as violent as most speculative fiction novels. But after the deed is done, the reader is let into Kvothe’s mind to justify his actions. This tactic let’s Rothfuss explain the killing in a chilling way, then explains Kvothe’s thinking and actions. In essence, this sets the reader at odds with Kvothe, makes them wonder why he is killing his family members, then explains it all away by showing what Kvothe knew that the reader didn’t—namely that this troupe wasn’t Edema Ruh. This tactic works because the payoff is quick in coming, not held from the reader for chapters and chapters. Rothfuss tells a story well, and he tells this one particularly well.

7. The theme of this novel is embracing the unknown, unknowable, and risk to gain knowledge and experience, but not being stupid about it. Kvothe doesn’t rush into battle against long odds, screaming and waving his arms. Rather, he plans and takes care and minimizes his risk, but still embraces the unknown to understand some known. Like when the element of surprise is lost in the bandit ambush, Kvothe makes the best of a bad situation, limits his exposure, but certainly has embraced some exposure just being there. A simple theme, sure, but supported well throughout the novel. This simplicity keeps the focus on the storytelling, as is appropriate for this book, which focuses everything on the storytelling.

8. As Garrett and I talked about this book, he brought up a point I wanted to write down for my own records: the past storyline is from Kvothe’s point of view moreso than many other first-person novels. For example, Devi is fairly one dimensional when introduced, but as the story progresses she gains more depth, especially here in the second book. This is because Kvothe understands more and more about her as time goes on. Kvothe is young and misunderstands people, categorizes them too rigidly on first meeting. But as with Denna beforehand, his understanding grows more accurate and wrinkled with more encounters. Kvothe is telling this story, so it makes sense that we only have his perspective on these characters he comes into contact with. This is initially off putting, making the characters seem one-dimensional on first meeting, but the payoff of seeing the characters grow more complex helps immensely to create reader’s trust in Rothfuss. The way he keeps everything so tightly focused through Kvothe’s perspective strongly supports the focus of the book being squarely on Kvothe's story.

9. In all, I found this book enjoyable, more so than the first. I think the pacing is perfect here, the writing improved, the characterizations more complex. I found the structure intriguing and appropriate to this biographical tale. The present storyline interludes continued to support the overarching mood of tragedy. I’m still curious about the story, and more so now. I look forward to the third book, and hope his writing improves even more.

For Isaac and Garrett.

1. So much sex. It felt like twenty percent of this novel was sex-scene. Three explanations spring to mind right off the bat: two pessimistic and probably wrong, one optimistic and probably right. First, perhaps Rothfuss was disappointed winning young adult literature awards for the last book, The Name of the Wind, and wanted to separate himself from that potential pigeon hole, so he added sex. Second, his audience grew four years since the last book, putting those young adults into puberty by now, and sex sells. These two pessimistic potential reasons are far from the simplest explanation though: it seems Kvothe is now 16, and sex is certainly a thing at that age. I believe this third reason, though there is still a lot of sex in this novel.

2. But Rothfuss writes the sex well: it lacks both sensationalism and stuffy moralizations. It’s not explicit, like George RR Martin is, but nor is it lightly implied and unconfirmed. He strikes a balance between the two that allows the sex to teach Kvothe much about himself, others, the world, history, the Fae, and morality. What I mean is that Rothfuss doesn’t moralize the sex, but through sex, Kvothe understands better how to treat other people and himself, how to do so morally—even in the differing morals of the different places and people he encounters. I want to say that he treats sex like he does magic and music, and mostly that’s true. It’s just that first sexual encounter with Felurian that potentially betrays that treatment. But even then, it’s treated like the first time Kvothe discovers his own music next to the pool in the forest, and his first sympathy in Ben’s cart. So yeah, the sex is treated like magic and music. It’s well done.

3. Rothfuss’ writing improves here: his sentence structures are slightly more complex, and he broadens the vocabulary he uses. This improvement is slight, but marked. It raises the quality from legible to readable—readable in the sense that I’m not constantly substituting words while reading it because I’m bored by his word choices, like I was in the first book. These minor changes increase the quality of the writing a lot. It’s a small change that makes the book much more enjoyable.

4. The improvement to the writing is necessary because this book is 1,000 pages long. If the writing hadn’t improved, this would’ve probably been a slog. One thousand pages is a long novel. Rothfuss uses 152 short chapters, averaging 6.54 pages per chapter. This is dangerous in that the short chapters break up the writing so much that it could feel like I’m constantly starting and stopping as a reader. By contrast, Martin uses long chapters to break up his long books: each is basically a short story. Here, each chapter is not short story: something happens in each chapter, something distinct, but it’s not quite as deep as a short story. Because Martin jumps around between characters in every chapter, he needs the longer chapters for supplementing his character building and making each chapter memorable so that when the book returns to that character a few chapters later, he doesn’t have to refresh the reader’s memory and slow down the story telling. Here Rothfuss sticks to Kvothe and keeps the story rolling, explaining even the travels between spaces in order to keep the focus on Kvothe’s story. It works for him with these short chapters.

5. Speaking of storytelling, Rothfuss is on fire here. Instead of a typical novel structure of one major crisis being built up, happening, then resolving, this is the story of Kvothe. He goes through many crises, resolves them, and then the novel stops. This isn’t a negative, because each portion of the book—college, Maer, bandit hunt, Fae, Adema, and college—are all self-contained novellas. In essence, this book is six novellas put together. Yet they’re all interconnected so closely that this novel works very well and the edges of each portion bleed into the next—most apparent at the end, when he returns to college and the story of his deeds in the other four portions catch up with him. This serial structure shows the novel's kinship to any series of short pulp fiction novellas. It could seem meandering if Kvothe didn't change from all of these experiences, but because he does, the novel is tight and a quick read.

6. As a character, Rothfuss shows and tells Kvothe well. The writing strikes a fine balance between showing Kvothe’s actions and reactions, and explaining Kvothe. One of Rothfuss’ tactics is borrowed from pulp fiction: he tells the action without letting the reader know the why, then explains it later. For instance, when Kvothe kills the troupe, it’s unclear to the reader what he thinks, why he’s angry. It feels very out of character for Kvothe and the novel, which is more violent than the first, but not as violent as most speculative fiction novels. But after the deed is done, the reader is let into Kvothe’s mind to justify his actions. This tactic let’s Rothfuss explain the killing in a chilling way, then explains Kvothe’s thinking and actions. In essence, this sets the reader at odds with Kvothe, makes them wonder why he is killing his family members, then explains it all away by showing what Kvothe knew that the reader didn’t—namely that this troupe wasn’t Edema Ruh. This tactic works because the payoff is quick in coming, not held from the reader for chapters and chapters. Rothfuss tells a story well, and he tells this one particularly well.

7. The theme of this novel is embracing the unknown, unknowable, and risk to gain knowledge and experience, but not being stupid about it. Kvothe doesn’t rush into battle against long odds, screaming and waving his arms. Rather, he plans and takes care and minimizes his risk, but still embraces the unknown to understand some known. Like when the element of surprise is lost in the bandit ambush, Kvothe makes the best of a bad situation, limits his exposure, but certainly has embraced some exposure just being there. A simple theme, sure, but supported well throughout the novel. This simplicity keeps the focus on the storytelling, as is appropriate for this book, which focuses everything on the storytelling.

8. As Garrett and I talked about this book, he brought up a point I wanted to write down for my own records: the past storyline is from Kvothe’s point of view moreso than many other first-person novels. For example, Devi is fairly one dimensional when introduced, but as the story progresses she gains more depth, especially here in the second book. This is because Kvothe understands more and more about her as time goes on. Kvothe is young and misunderstands people, categorizes them too rigidly on first meeting. But as with Denna beforehand, his understanding grows more accurate and wrinkled with more encounters. Kvothe is telling this story, so it makes sense that we only have his perspective on these characters he comes into contact with. This is initially off putting, making the characters seem one-dimensional on first meeting, but the payoff of seeing the characters grow more complex helps immensely to create reader’s trust in Rothfuss. The way he keeps everything so tightly focused through Kvothe’s perspective strongly supports the focus of the book being squarely on Kvothe's story.

9. In all, I found this book enjoyable, more so than the first. I think the pacing is perfect here, the writing improved, the characterizations more complex. I found the structure intriguing and appropriate to this biographical tale. The present storyline interludes continued to support the overarching mood of tragedy. I’m still curious about the story, and more so now. I look forward to the third book, and hope his writing improves even more.

Labels:

2011,

Fantasy,

Kingkiller Chronicles,

Patrick Rothfuss

08 January, 2016

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

For Gunn.

1. This book is uproariously funny! Full on belly laughs in every chapter all the way through. I seem to be having trouble getting people to believe me on this, especially those who have a rigid conception of Austen but have not read this book. Let me put it to you this way: Austen makes a penis joke in the third line of the novel. Here are the first three lines:

2. The structure of the novel is a straight narrative in that the novel progresses linearly from start to finish, with only these funny asides to break the flow. This structure works for her story because it allows these asides to stick out like sore thumbs and ensure the reader that she’s satirizing the whole way through.

3. The writing is good: she has a wonderful way of writing the narrative, and her fourth-wall-breaking parts are uproariously funny and well paced. Austen does this thing where she often summarizes dialogue, and it works well:

4. Austen’s character creation is strong. Mr. Thorpe, Isabella, Henry, the General, and Catherine are all distinct characters who are different people. Austen does this through describing them immediately, but not with the usual blazon. Rather, she describes their character, what makes them tick. With Isabella, her tactic is a little different in that Austen shows her character very effectively through her actions and reactions. Like any Austen book that I’ve read, her characters all make sense and seem realistic for the situations and time period that they exist in.

5. In all, this is a good book. It’s hilarious and well written, structured simply but effectively, and contains good characters. But I fear it’s too referential to be a great book: if you aren’t familiar with Gothic novels and Rousseauian sensibilities, the jokes will fall flat and this will seem like a poor Austen novel. However, for somebody who has read some of those, or is at least familiar with them, this novel is a real treat: a wry, satirical look at the Gothic sensibilities with just a hint of bitterness.

1. This book is uproariously funny! Full on belly laughs in every chapter all the way through. I seem to be having trouble getting people to believe me on this, especially those who have a rigid conception of Austen but have not read this book. Let me put it to you this way: Austen makes a penis joke in the third line of the novel. Here are the first three lines:

No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy would have supposed her born to be an heroine. Her situation in life, the character of her father and mother, her own person and disposition, were all equally against her. Her father was a clergyman, without being neglected, or poor, and a very respectable man, though his name was Richard—and he had never been handsome.See! Dick joke! And from there things just get more funny and more anti-sentimentalism and more antagonistic to Gothic novels. The whole thing is a hilarious satire of sentimentalism and Gothic novels. Catherine imagines many dark doings around her. Austen delights in saying that Catherine should arrive home in a train of unimaginable wealth and glory, per the Gothic sensibility, but she doesn’t. Every Gothic-esque situation she gets into turns to her shame and embarrassment because she lets her imagination run wild. Austen continually breaks the fourth wall to point out what other novels show she should be writing, illuminating the tropes of Gothic tropes, then subverts them clearly in order to show her disgust at those tactics. And this of course brings the theme of life not being a novel to the fore. It’s almost bitter, but continually hilarious throughout. The most notable part is the whole second half of chapter five, where she breaks the fourth wall to take novel writers and critics to task for decrying novels in their own works. Here is a small portion of that truly funny portion:

Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard? I cannot approve of it. Let us leave it to the reviewers to abuse such effusions of fancy at their leisure, and over every new novel to talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans. Let us not desert one another; we are an injured body.

2. The structure of the novel is a straight narrative in that the novel progresses linearly from start to finish, with only these funny asides to break the flow. This structure works for her story because it allows these asides to stick out like sore thumbs and ensure the reader that she’s satirizing the whole way through.

3. The writing is good: she has a wonderful way of writing the narrative, and her fourth-wall-breaking parts are uproariously funny and well paced. Austen does this thing where she often summarizes dialogue, and it works well:

She was looked at, however, and with some admiration; for, in her own hearing, two gentlemen pronounced her to be a pretty girl. Such words had their due effect; she immediately thought the evening pleasanter than she had found it before—her humble vanity was contented—she felt more obliged to the two young men for this simple praise than a true-quality heroine would have been for fifteen sonnets in celebration of her charms, and went to her chair in good humour with everybody, and perfectly satisfied with her share of public attention.This tactic works by telling the reader exactly what’s important, instead of showing them the effect the dialogue had on Catherine. Austen tells very well.

4. Austen’s character creation is strong. Mr. Thorpe, Isabella, Henry, the General, and Catherine are all distinct characters who are different people. Austen does this through describing them immediately, but not with the usual blazon. Rather, she describes their character, what makes them tick. With Isabella, her tactic is a little different in that Austen shows her character very effectively through her actions and reactions. Like any Austen book that I’ve read, her characters all make sense and seem realistic for the situations and time period that they exist in.

5. In all, this is a good book. It’s hilarious and well written, structured simply but effectively, and contains good characters. But I fear it’s too referential to be a great book: if you aren’t familiar with Gothic novels and Rousseauian sensibilities, the jokes will fall flat and this will seem like a poor Austen novel. However, for somebody who has read some of those, or is at least familiar with them, this novel is a real treat: a wry, satirical look at the Gothic sensibilities with just a hint of bitterness.

05 January, 2016

The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss

For Isaac and Garrett.

1. Rothfuss tells this story mostly well. The story is interesting, with a satisfying number of things going on. Each chapter adds to some part of the narrative. There are various interesting characters and experiences. But some aspects feel like a foregone conclusion. For instance, the main character makes a few claims that things don’t work out like they do in a story—but they totally do here: Denna’s attraction to Kvothe surprises nobody except Kvothe; Kvothe’s slaying of the cow-beast thing works just like it has a hundred times before in books; everytime Kvothe is down to his last penny, some stroke of luck grants him reprieve from starvation. These lucky breaks annoy me a bit, as do his wry observations about storybook tales being constantly undermined. However, they manage to stay just this side of deus ex machina: the beast being killed accidentally and costing Kvothe much more than he anticipated, getting a whole silver talent as a beggar then getting it beat out of him, running into and losing Denna again and again. Rothfuss keeps the tale from relying too much on deus ex machina, but still manages to weave some surprise into the novel. This is done passably, but in all, the story is pretty good. I enjoyed it and it certainly kept me reading. It was exciting without a big body count, and that’s refreshing.

2. The structure of the story is pretty interesting. There are two timelines going on: the present-day and the past. In the present, the area Kvothe lives in is nebulous and torn apart by wars and weird creatures, while in the past the tale shows young Kvothe growing up. I assume that at the end of the third book, these two storylines will meet. But this allows Rothfuss to drop hints and foreshadow heavily. For instance, we know at one point that Kvothe will kill a king, get expelled from the University, and lose Denna irrevocably. But at this point, we don’t know why or how or when any of this will happen. This helps add to the way the book keeps me reading. The heavy foreshadowing shows this book for what it is: pulp fiction. But the structure is interesting and really works well.

3. Rothfuss even foreshadows that the tale is switching from present to past and staying there for a long time in the way Kvothe warns Devan that the tale will take three days to tell. This switch is a real risk for the author. It occurs around twenty percent into the book and it’s a major shift: basically restarting the book with new characters in a new place, changing the tone entirely, and not referring back to the present day world he’s already built explicitly. This is a real risky point where Rothfuss could’ve lost the reader easily, but he uses three pages to explain Devan’s appointment and Kvothe’s unwillingness to adhere to Devan’s time schedule. This explains to the reader what is coming. From there, the narrative is mostly in the past, with brief interludes into the present timeline. It’s well done.

4. Unfortunately, the writing is poor. Well, that’s not entirely fair. The writing is fine, but it’s pulp fiction writing. This novel won an award for Young Adult literature and Rothfuss’ vocabulary is limited, but not overly so. He even tries his hand at a few interesting tactics: specifically some nice repetition and some consonance. So it’s interesting for me to read as an adult. But I can also see my teenage boy self liking it more than I did.

5. One area where he steps away from traditional pulp fiction is in his characterizations. Nobody is perfect, nobody is wholly evil. The Fae are humanized by Bast, while Denna has a crooked nose. She is the love interest and, as such, Kvothe looks at her through rose-colored glasses, but Kvothe’s friends point out that she is cruel and has a crooked nose. She’s not perfect, and neither is Kvothe, and that’s a positive for the story. It somehow feels more honest, even with the storybook aspects Rothfuss has in there.

6. The theme seems to be some sort of call to find the silver lining in everything. I mean, this seems to be Rothfuss’ conclusion most of the time. Kvothe decides to be satisfied with how much time he gets to spend with Denna. He is satisfied with his paltry rainy day fund while homeless. At college he isn’t satisfied with being banned from the Archives, but he finds ways to work with it and doesn’t let it eat him apart. His whole family is murdered and he finds a healthy way to deal with it—it even teaches him about other people in a very important way. I guess this list shows that the theme is more about how to handle what life throws at you and turn all to your advantage, no matter how small that advantage. It’s about the importance of turning a negative into a positive, owning your faults in the sense of learning from them and when to allow them, and keeping a positive attitude.

7. I have some friends who consider this their favorite book, and I can see that. I know I have said some critical things so far, but it’s a cracking read and a good book: very exciting without being overly violent for the built world, and it kept me reading way past my bedtime. It has enough going on, enough threads to keep me reading. Being interested in the story and world from reading this book, I will be immediately reading the next one. This one is a good book.

1. Rothfuss tells this story mostly well. The story is interesting, with a satisfying number of things going on. Each chapter adds to some part of the narrative. There are various interesting characters and experiences. But some aspects feel like a foregone conclusion. For instance, the main character makes a few claims that things don’t work out like they do in a story—but they totally do here: Denna’s attraction to Kvothe surprises nobody except Kvothe; Kvothe’s slaying of the cow-beast thing works just like it has a hundred times before in books; everytime Kvothe is down to his last penny, some stroke of luck grants him reprieve from starvation. These lucky breaks annoy me a bit, as do his wry observations about storybook tales being constantly undermined. However, they manage to stay just this side of deus ex machina: the beast being killed accidentally and costing Kvothe much more than he anticipated, getting a whole silver talent as a beggar then getting it beat out of him, running into and losing Denna again and again. Rothfuss keeps the tale from relying too much on deus ex machina, but still manages to weave some surprise into the novel. This is done passably, but in all, the story is pretty good. I enjoyed it and it certainly kept me reading. It was exciting without a big body count, and that’s refreshing.

2. The structure of the story is pretty interesting. There are two timelines going on: the present-day and the past. In the present, the area Kvothe lives in is nebulous and torn apart by wars and weird creatures, while in the past the tale shows young Kvothe growing up. I assume that at the end of the third book, these two storylines will meet. But this allows Rothfuss to drop hints and foreshadow heavily. For instance, we know at one point that Kvothe will kill a king, get expelled from the University, and lose Denna irrevocably. But at this point, we don’t know why or how or when any of this will happen. This helps add to the way the book keeps me reading. The heavy foreshadowing shows this book for what it is: pulp fiction. But the structure is interesting and really works well.

3. Rothfuss even foreshadows that the tale is switching from present to past and staying there for a long time in the way Kvothe warns Devan that the tale will take three days to tell. This switch is a real risk for the author. It occurs around twenty percent into the book and it’s a major shift: basically restarting the book with new characters in a new place, changing the tone entirely, and not referring back to the present day world he’s already built explicitly. This is a real risky point where Rothfuss could’ve lost the reader easily, but he uses three pages to explain Devan’s appointment and Kvothe’s unwillingness to adhere to Devan’s time schedule. This explains to the reader what is coming. From there, the narrative is mostly in the past, with brief interludes into the present timeline. It’s well done.

4. Unfortunately, the writing is poor. Well, that’s not entirely fair. The writing is fine, but it’s pulp fiction writing. This novel won an award for Young Adult literature and Rothfuss’ vocabulary is limited, but not overly so. He even tries his hand at a few interesting tactics: specifically some nice repetition and some consonance. So it’s interesting for me to read as an adult. But I can also see my teenage boy self liking it more than I did.

5. One area where he steps away from traditional pulp fiction is in his characterizations. Nobody is perfect, nobody is wholly evil. The Fae are humanized by Bast, while Denna has a crooked nose. She is the love interest and, as such, Kvothe looks at her through rose-colored glasses, but Kvothe’s friends point out that she is cruel and has a crooked nose. She’s not perfect, and neither is Kvothe, and that’s a positive for the story. It somehow feels more honest, even with the storybook aspects Rothfuss has in there.

6. The theme seems to be some sort of call to find the silver lining in everything. I mean, this seems to be Rothfuss’ conclusion most of the time. Kvothe decides to be satisfied with how much time he gets to spend with Denna. He is satisfied with his paltry rainy day fund while homeless. At college he isn’t satisfied with being banned from the Archives, but he finds ways to work with it and doesn’t let it eat him apart. His whole family is murdered and he finds a healthy way to deal with it—it even teaches him about other people in a very important way. I guess this list shows that the theme is more about how to handle what life throws at you and turn all to your advantage, no matter how small that advantage. It’s about the importance of turning a negative into a positive, owning your faults in the sense of learning from them and when to allow them, and keeping a positive attitude.

7. I have some friends who consider this their favorite book, and I can see that. I know I have said some critical things so far, but it’s a cracking read and a good book: very exciting without being overly violent for the built world, and it kept me reading way past my bedtime. It has enough going on, enough threads to keep me reading. Being interested in the story and world from reading this book, I will be immediately reading the next one. This one is a good book.

Labels:

2007,

Fantasy,

Kingkiller Chronicles,

Patrick Rothfuss

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg/640px-View_of_the_Acropolis_Athens_(pixinn.net).jpg)

.jpg/308px-Lute_(by_Princess_Ruto%2C_2013-02-11).jpg)