1. Unlike Cherryh’s typical character focus, this novel discusses a situation over a long time-span of 305 years. The situation is a new colony on a habitable nut little understood planet. The book starts with it being founded, flourishing, and collapsing. Then being rediscovered, studied, and collapsing again. Then, between the on-screen scenes, being rebuilt and thriving. In Cherryh's universe, the science fiction theme clearly test-runs theories of first contact, and studies how azi and humans react to collapse. In this way, I think this is the most space operatic novel I’ve read by Cherryh, though her whole Alliance-Union universe tends towards this sub-genre as all the books are so interlocked.

From Section D: Mission Report by Dr. Cina Kendrick

Intelligence is not, as indicated above, a scientific term. [...]

Two considerations must be made. First, that an organism’s behaviors may be survival-positive in one environment and not in another, and second that its perceptive apparatus, its input devices, may be efficient for one environment but not for another. The quality imprecisely described as intelligence is commonly understood to describe the generalization of an organism, ie, its capacity to adapt by the use of analogy to a variety of situations and environments.

On the contrary, even the concept of analog is anthropocentric. Logic is another anthropocentric imprecision, the attempt to impose an order (binary, for instance, or sequential) on observations which themselves have been filtered through imprecise perceptive organs.

The only claim which may be made for generalization as a desirable trait is that it seems to permit survival in a multitude of environments. The same may be said of generalization as part of the definition of intelligence, particularly when intelligence is used as a criterion of the inherent value of an organism or its right to life or territory when faced with human intrusion. Generalization permits migration in the face of encroachment; and it permit one species to encroach on another, which adds another dimension to natural selection. But when extended to intrusion not over another mountain ridge within the same planetary ecology and the same genetic heritage, but instead to intrusion of one genetic heritage upon another across the boundaries of hitherto uncrossable space, this value judgment loses some credibility.

2. However, this novel isn’t all situational—well-developed characters still fill the pages. But it’s character by mindset more than specific individuals. Characters who take a non-interventionist policy oppose those who take a more helpful role, and both camps contain exploitative characters. These ideas are spread through the novel: from Union’s first contact with the Calibans, to Alliance's first contact with the Gehennans, to Gehenna's first contact with the Unioners, to Farsider’s first contact with a Gehennan.

—First, the Union colonists’ ignorance leads them to assume that the Calibans are stupid. This allows catastrophic destruction of the Union mission—both in the slow trickle of children away from their control, and the base being physically undermined and collapsing.

—Second, the Alliance comes in slow and indecisive—non-interventionist in word, but not so much in deed. Their base is way too close for comfort and their observation post changes what they observe. Their confidence in their space-based surveillance is similarly poorly placed—they can see the whole, but no details and are just as ignorant as to the meaning of the whole. Like when McGee heals Elai’s leg, it’s half-assed through indecision: in her own misplaced confidence and self-conflicted desire to save a child’s life, she doesn’t search for or get out the near-fatal bone-spur. This fumble sets her mission back fifteen years, until Elai’s mother dies. The Alliance's indecision as a whole leads to war, death, and the destruction of half the Gehennan culture. Finally, both the Alliance and Gehennans decide to educate and put their pride aside enough to be educated, and that seems the right track. (I read McGee’s pattern as a clear step in this direction.)

—Third, the Union comes in hungry for knowledge and offering trade. Elai rightly recognizes that the Union needs nothing from her, and calls their bluff. This is entirely the wrong foot to start out on for the Union: the wary reaction of the Calibans—leading to the Unioners further fear-based reaction—illustrates this. The Union is still ignorant to the point of not knowing how to engage their potential teacher, and this ultimately loses them their final influence over the colony.

—Fourth, the Farsiders appear to find the Gehennan curious, but the knowledge they do have—from videos and reports—allows even the rough docksiders to avoid an incident. Similarly, the Gehennan and Caliban pair chosen for the visit are appropriate for the high number of strangers they expect to run into.

—McGee, Genley, Elai, Pia, Jin, Jin Younger, Jin Elder, and Scar are the main characters, but the mindsets clearly steal the show from the people. These are well constructed, interesting characters; but they are not as important to the novel as the mindsets.

—And I find this discussion of the mindsets of First Contact to be the theme of the novel. First Contact here is a metaphor for the other. In our day-to-day lives we are consistently pushed outside of our normal comfort zones to deal with unfamiliar people, opinions, situations, etc. There are two ways this typically goes: fear or understanding. Education and embracing the unknown—quite literally in McGee’s case—leads to an inclusion that grows knowledge and culture. Fear leads to death. That’s Cherryh’s point and she makes it well throughout the novel by focusing on the mindsets—though she doesn’t lose sight of the individual characters in a way that shows how small acts have large consequences. Humanity will survive because it has generalization, but that's not always a good thing when the situation or environment pushes us, even on an easy, habitable, fruitful planet like Gehenna.

3. Cherryh set herself a hard task in the various writing tactics of this novel. She includes memos and portions of scientific papers to show the affect actions have on the whole.

I propose that, instead of arguing old theories which have considerable cultural content, we consider this possibility: that humanity develops a multiplicity of answers to the environment, and that if there must be a system of polarities to explain the structure around which these answers are organized, that the polarity does not in and of itself involve gender, but the relative success of the population in curbing those individuals with the tendency to coerce their neighbors. Some cultures solve this problem. Some do not, and fall into a pattern which exalts this tendency and elevates it, again by the principle that survivors and rulers write the histories, to the guiding virtue of the culture. It is not that the Cloud River culture is unnatural. It is fully natural.Another aspect is researchers’ notes:

Is even childhood one of our illusions? Or is this forced adulthood what’s been done to us out here?And memos also fill the pages, at least one going through draft after draft showing McGee’s mindset and final words, exposing much about her character and her dissatisfaction with the powers over her. Further, the Union, Alliance, Styxside, and Cloud River cultures all have their own voices, and the latter two communicate also via hand gestures and drawing patterns. It’s a plethora of writing tactics, causing Cherryh to switch gears consistently in a way that keeps the writing all fresh and exciting. It’s not all one voice, though Cherryh’s typical tightly focused voice is on display fully.

Us. Humans. They are still human; their genes say so. But how much do genes tell us and how much is in our culture, that precious package we brought from old Earth?

What will we become?

Or what have they already begun to be?

They look like us. But this researcher is losing perspective.

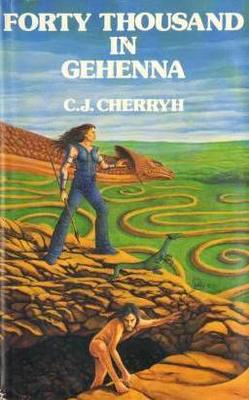

4. Many of these memos and papers take the place of actions and interior monologue in a way that makes the novel seem a little slow. There’s a lot that happens over these three hundred and five years, but most of the novel is people reacting to those changes and settling in as best they can. The action is usually fast—a couple of pages—and decisive, leaving the bulk of the novel to unraveling the meaning of those actions and what they signify. This isn’t necessarily a negative as I was enthralled throughout, but covers that show a human riding on a dragon-like creature mislead and that first edition cover (at the top) is the most informative as to what the novels feels like. Not sedentary, but also not rollicking, despite what the following cover wants you to believe:

5. This is a good novel. I wanted a bit more action and a bit more psychological depth—Jin Elder and McGee are really the only two who have any depth. But then, maybe that is me projecting on the novel too much of Cherryh’s other works, kind of like how Union and Alliance project on the Gehennans too much of their empirical data. I like seeing Cherryh trying a new method of storytelling with the time span that disallows her usual deep individual psychology, but I think her strengths primarily rest in the other way she writes. That’s not to say this isn’t a wonderful novel, because I really enjoyed it. It’s certainly better than other situational novels I’ve read, like The Plague by Albert Camus.

_3.jpg/640px-Komodo_dragon_(Varanus_komodoensis)_3.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment