This is about all five of the books in the Song of Ice and Fire series:

1. A Game of Thrones

2. A Clash of Kings

3. A Storm of Swords

4. A Feast for Crows

5. A Dance with Dragons

Because they are a continuous story and series, and they are so similar, I have chosen to talk about them as a whole instead of five separate books.

1. I find a distinction between a good writer who chooses words well and varies sentence structures interestingly, and a good storyteller—a writer who paces himself well, constructs the story in a clever way, and does not let a big story point become forgotten. Martin is the latter, not the former. For instance, the twincest is a big plot point, but it is never forgotten and never unimportant—and not in a sensational way, or not in a wholly sensational way. It is not a cheap, egotistical writer's trick, "Look at me! I will tackle even incest between twins! How courageous I am!" Rather, it is a major plot point and a fulcrum for the entire story. But the absolute best thing that George RR Martin does is his structure of sequential chapters from different characters' points of view. I have not seen this before in writing, so let me explain exactly what this is: in Chapter 28, Cat comes back from hearing that Tyrion probably attempted to murder her son, and ends up finding Tyrion on the road, so she kidnaps him; Chapter 29 is a royal tournament, told from the point of view of Cat's daughter; Chapter 30 concludes the royal tournament from Ned's point of view, and continues the thread of Ned's investigation; then Chapter 31 returns us to Cat and Tyrion, this time, however, the chapter is from Tyrion's point of view, with maybe two weeks to a month of time elapsed after he was kidnapped—there was as much time between his kidnapping and Chapter 31 as time spent in Chapters 29 and 30, which dealt with other story arcs. This is how the entire series is written. Every single chapter. This is brilliant and well done. I do not think I've come across somebody else who builds their chapters this way, and it's incredibly effective. This structure fits and maybe even encourages the complexity of the story. As a writer, I wonder at how much time Mr. Martin spends making sure that he has his facts straight, his chapters sequential, and his lore correct? This is complex stuff and he pulls it off. I would say 90% of that success is because of the fantastic chapter structure—he realized that with his complex plot, he would need this straightforward chapter system to keep everything legible.

2. On the other hand, the writing is not great. It communicates, and at times characters have their own voices, but on the whole its unremarkable. The writing begins in Book 1 as merely OK, then gets progressively better until the end of Book 1—but it never gets great except for these four paragraphs, which I think are stunning and beautifully written:

“Raid him here,” he said, pointing. “A few hundred men, no more. Tully banners. When he comes after you, we will be waiting”—his finger moved an inch to the left—“here.”I think this section is good writing. It is strong, describing something physical as "a hush", which describes the atmosphere that physical thing creates. But it's not as trite as the typical use of this tactic: "a painful-looking sword"—blech. Martin lists well: lists of characters at an event, tournament entrants, and lists like the one above—a small list to focus in on an event. This one repeats "here": describing it first as a future plan, then as a location, then as a relationship, then as an action. Using one word four times in four different ways was an effective way to build the tension and describe the emotions and perspective of the main character, while still describing the setting. Books 2 and 3 are a little less interesting to me for their writing than the last quarter of Book 1. The writing quality seems to go slowly downward, but this could easily be explained by the two year publishing schedule—Book 2 came out two years after Book 1, and Book 3 two years after that. Books 4 and 5 are mostly the same quality as the last quarter of Book 1 in terms of the writing, but there are some parts that are worse. In all five books published so far, nothing matches the beauty of that passage above from Book 1. However, at the end of reading all five, I remember two points were the writing was particularly bad. Perhaps once every 20 chapters or so I come across to phrase that makes me laugh aloud, and these two are the worst: at one point the phrase "man staff" describes a character's erect penis; and in describing a morning he writes, "The day was gray, overcast." These are both ridiculous. The second shows his tendency to insult the reader by over-explaining things as if they were idiots. But, so far this series is 4,273 pages, and there is going to be some ridiculous stuff in all that space. I am truly surprised that there is not more ridiculous writing, and I am also surprised that there is not more poetic beauty.

Here was a hush in the night, moonlight and shadows, a thick carpet of dead leaves underfoot, densely wooded ridges sloping gently down to the streambed, the underbrush thinning as the ground fell away.

Here was her son on his stallion, glancing back at her one last time and lifting his sword in salute.

Here was the call of Maege Mormont’s warhorn, a long low blast that rolled down the valley from the east, to tell them that the last of Jaime’s riders had entered the trap.

And Grey Wind threw back his head and howled.

3. The female characters are strong, well written, and believable without pandering to a single sense of "femininity". This is achieved through having multiple female characters—Sansa is a demure dreamer, Cat is a dutiful realist, Lysa is a protective paranoid, Arya is a free spirit—the females are as varied as the males, and as important. I heard somewhere that he wrote the females by just writing characters, and their gender was almost incidental after that. I don't know if that's true or not. But, to me, it seems like they are all women, through and through—though maybe that's because of the varied spectrum of female characters presented.

4. A major complaint about the series is a lack of a moral, or driving central theme. I don't think that's fair. Partway through Book 3 I wrote my notebook, "There are consequences. I think this is an important distinction: the gods do not appear powerless, though not all powerful either, but there are consequences to gaining their favors or boons or help. Satisfying a desire requires sacrifice—acquiring a desire requires prioritization, sacrifice, skull sweat, self examination, open eyes, planning, and maybe some money." After five books, I do think this is the central theme: you can't shake your past and you have to sacrifice on the altar of the future. One character searches for truth and ends up executed because the truth concerns those who could execute him, and his past complicated matters. Cat looks for the hand behind the attempted assassination, but her past history seduces her into believing lies, and in her desire to satisfy her curiosity she sacrifices the realm on the altar of the future. Every story arc, every character, every plot point comes back to the necessity of sacrifice. Sometimes the consequences are foreseen, and sometimes they are not.

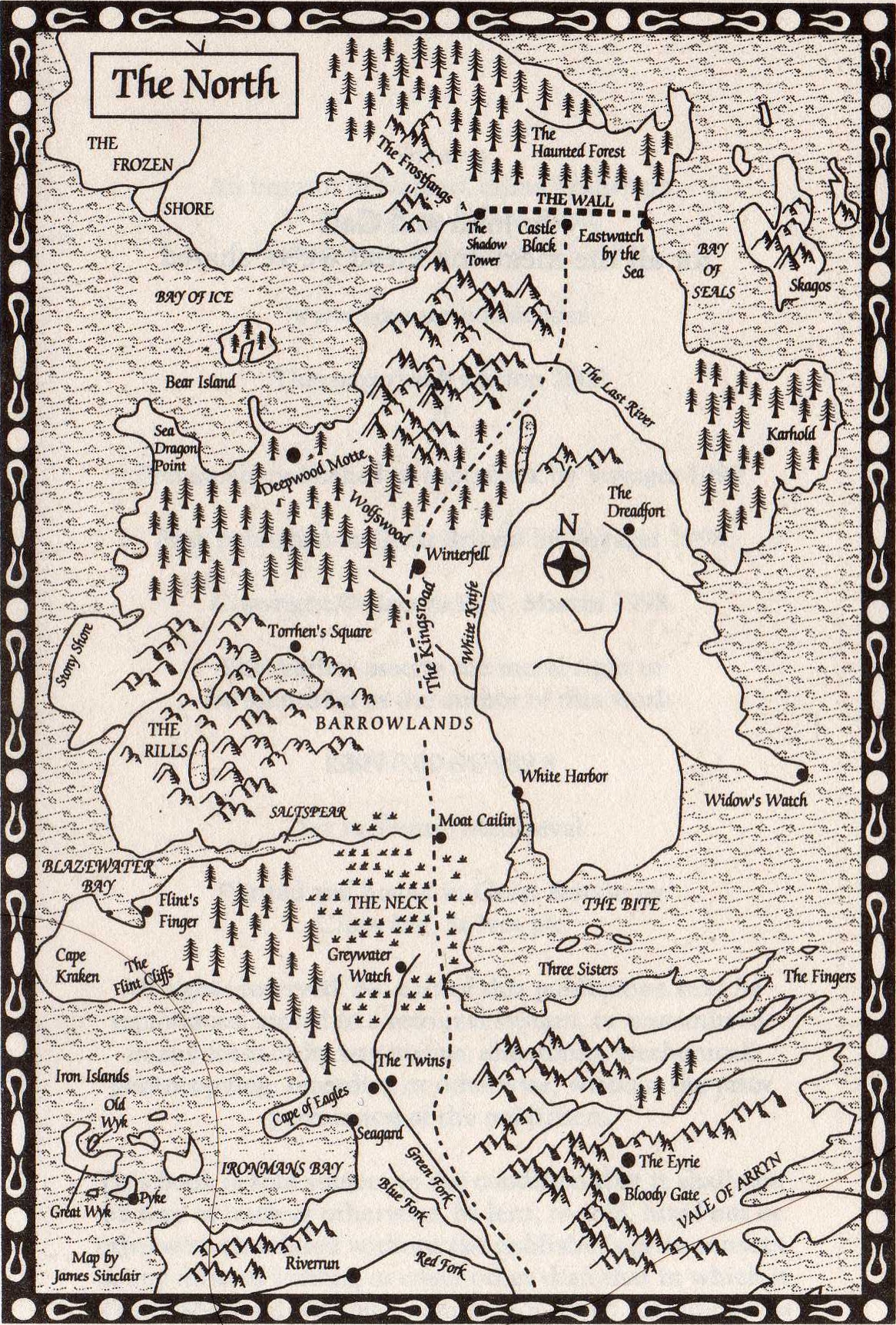

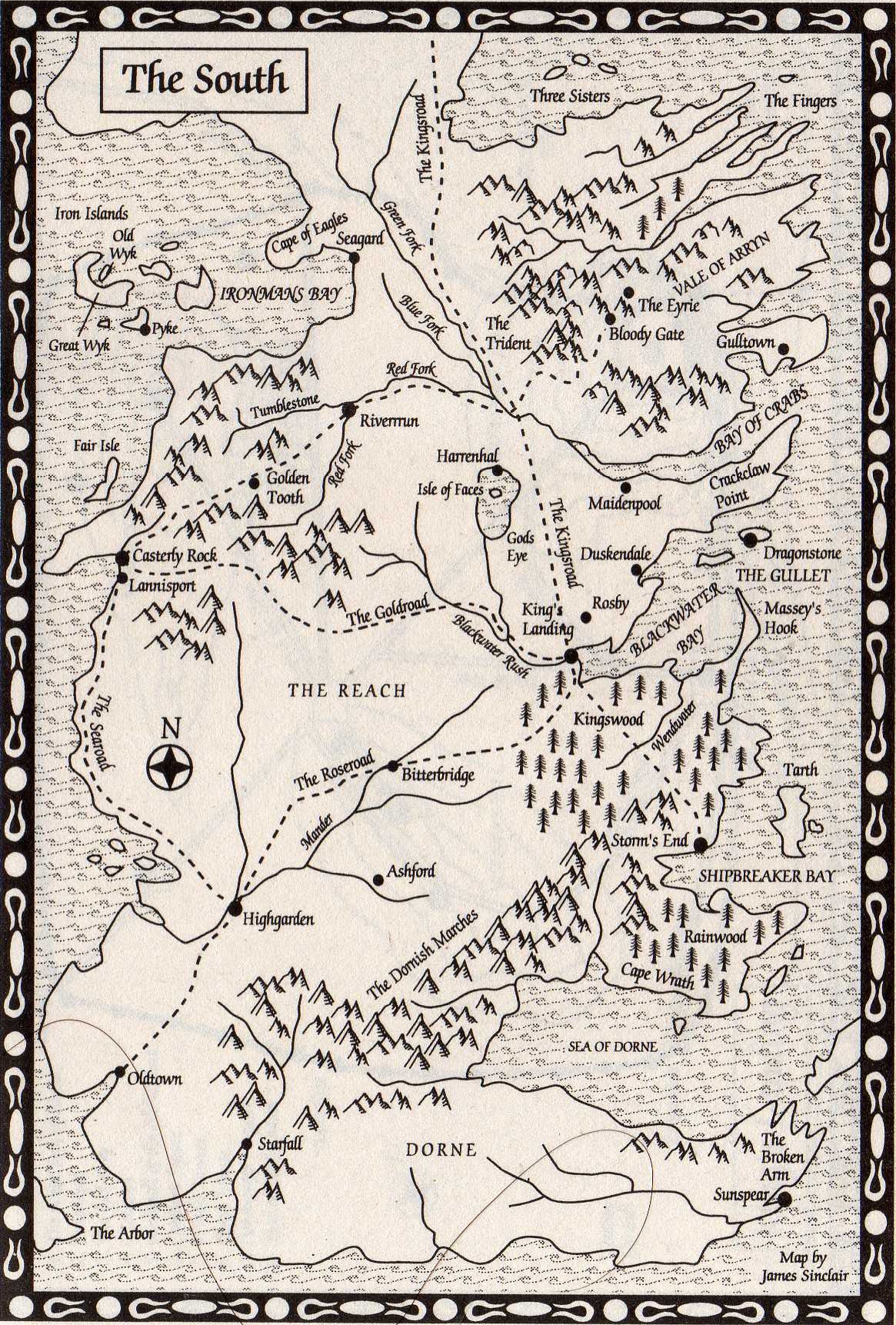

5. It has a map. But unlike most science fiction, this map is always important, and actually helpful. Brilliant and fun.

6. I question whether this is sensational. The sensational aspects are big plot points, and important to the story and the characters. So, yes, it is sensational in twincest and pushing young boys out of windows. But I don't believe that it is sensational simply to be sensational or edgy or unique. I think it's trying to be realistic, important, and not clichéd. So is its sensationalism a fault or not? On one hand, the density of sensational situations is too low for me to say that it is faulty, but it's also too high for me to say that it is not. However, for every sensational plot point, there are reverberations felt throughout the rest of the novels. I mean, the twincest is still affecting characters at the end of Book 5 in very significant ways. So whether it is faulty or not, he effectively uses the sensational plot points to drive the characters and story throughout.This is good work by Mr. Martin, and I think it is effective.

7. Like in the Count of Monte Cristo, something happens in every chapter that will echo into further chapters. Nothing is forgotten—which leads to fanboy-argumentative levels of complexity. Sure, some chapters are more important than others, but all have importance. There are no dead chapters.

8. Martin's writing is often a good mix of showing and telling. But he sometimes tends to redundancy here: sometimes the telling is after the showing, which means that the telling is supported by the showing or the showing is explained by the telling. But it feels like he's sometimes insulting the reader's intelligence by redundancy.

9. He tries to make every character sympathetic, but ends up making each unsympathetic. I actually like this. It lets the reader decide which characters are bad or good, a trust which softens the blow of insulting over-explanation. This is very effective.

10. Without direct foreshadowing, he foreshadows well. One character is obsessed with knights and marrying, and she ends up often interacting with knights and getting married once and almost married twice. However, it doesn't quite work out like she wanted it to. Another character is working towards a clash with a couple of the other groups of characters, which I fully understand is coming, but I do not know how or when it will happen. This indirect foreshadowing is done well, effectively drawing me through the story to find the closure that I know is coming.

11. The pacing pulls me along–each chapter ends on a bit of a cliffhanger. It drives the fine line between resolution and mystery enough to keep me going. I want to keep reading and see how the story from this chapter ends, which might be continued after an interlude of two or three more chapters, but by the time I'm done with the next chapter, I want to see how the story from that chapter ends, and the next one too. I think the length of the chapters helps him thread this line. In Book 1, each chapter is about half an hour, and in later books they are about 45 minutes each.

12. Despite his unimaginative word choices, his descriptions are good because he makes what he describes interesting. The list of knights in the hand's tourney is interesting—the sigils and armors and various body types of knights are varied and informative about their personalities, families, and homeland cultures. Though they're all Westerosi, there are differences between Westerosi of different places, and these types of descriptions really help flesh out the world. And he describes interesting characteristics of them in uninteresting ways. One man's sword is lit on fire before the melee, but it's sort of just burning there, not really described remarkably.

13. Like the Count of Monte Cristo, Martin breaks the narrative up with storytelling interludes. They break up the complex drama of the main story in little chunks of straightforward storytelling like old Nan's stories, or Meera's stories, or the stories of Ygritte. These are all welcome interludes that provide context and back story and history, but also breathing space and a break from the overarching complexity. Most are interesting and well done.

14. Contrasting the almost insulting over explanation of basic things, the reader is trusted with more information than some characters at times—why Bran fell, the death of Rickon and Bran, the twincest. This leads to a few "don't go in there!" moments, but it happens so rarely that it does not get old or seem like a cheap trick. Maybe this is a lesson to draw from it—some cheap tricks please the reader and, used sparingly, can feel like good storytelling or writing. This applies both two extra information and sensational plot points. Back to the Count of Monte Cristo, the mystery of who is who while the count is disguised also does this well.

15. Like with the female characters, I think variety is key to the whole series. The various male characters, different families, and varied plot points, experiences, and revelations spread throughout keep things interesting and readable. This is very effective for a long, complex novel series like this.

16. I like how each character's chapter can almost stand on its own—though Danerys more than most. However, they're so interconnected that they work much better together. [This relates back to the chapter structure outlined in point number 1.] Daenerys story acts as an ongoing example of those interludes I was talking about in point 13: through the first three books, her story is an interesting respite from the complexity of the Westerosi intrigues.

17. The slow pacing makes a book feel no less exciting or important. Like the Iliad, this is ponderous, narrow in scope, and full of importance—rather than fast, full of broad brush strokes, and lacking anything of import to think about. With the first book, it felt like this was the interesting, important bit of a much larger tale—like when Achilles kills Paris. Now, after all five books, I still feel like this is paced well, important, and interesting. The slow pace helps keep the complexity comprehensible, the variety of characters keeps the plot moving because when one is asleep another is doing something interesting, and the slowness encourages me to pay close attention to each part. In short, the pacing fits the setting, the plot, and the complexity. This works well.

18. The setting is believable—but even more than that, it's tangible. He creates a world and cultures from recognizable parts and pieces. Westeros is essentially the British isles, with Alaska tacked onto the top—land bridge and all—and both the Sinai Peninsula and Italy tacked onto the bottom. Europe is gone, and in its place across the English channel is now the Russian steppes and some major island countries from the Mediterranean. The Crows' Wall is Hadrian's Wall. The people are relatable too: they eat garlic and cows and other foods that we know today. It's inspired by the War of the Roses. The examples go on and on. This takes the world beyond believable to tangible, understandable, and effective.

19. Death lacks teeth. By the time of the Red Wedding, so many characters have died and come back to life that I'm not certain any of those killed in the Red Wedding are really dead—and not all of them are. Bran, Rickon, Aria, the three convicts in that cart, the lightning lord, the Crows who come back as wights, et cetera. These resurrections steal some of the drama and import from death. But death lacking teeth also helps build the world – so many of these characters face death on a daily basis as their job, or as the result of their desires, that to treat every single death as the massive plot point that the book is centered around would be unfair. Death is commonplace in the book because it is commonplace in Westeros.

[Added 8/31/15:

19. One other thing Martin does well is to forgo describing nights as lonely: describing times, places, or tableaux by the perspective of the point of view character on it. Rather, he factually states, "the day was gray," then allows the events, actions, and interior interactions of that day and the characters to color the whole in the reader's mind. Like in the beautiful, lengthy passage quoted in point two above, he simply describes the facts and therefore shows the scene with such specificity that he sets the mood without ever stating it. Cat is lonely in that passage, and anxious, and he does not have to spell that out explicitly, so he doesn't.]

_von_Anhalt.jpg/438px-Codex_Manesse_(Herzog)_von_Anhalt.jpg)

%2C_f.40_-_BL_Cotton_MS_Nero_D_IX.jpg/648px-Jean_de_Saintr%C3%A9_jousts_with_Enguerrant_-_The_Romance_of_Jean_de_Saintr%C3%A9_(c.1470)%2C_f.40_-_BL_Cotton_MS_Nero_D_IX.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment