17 September, 2018

A Voice from the Main Deck by Samuel Leech

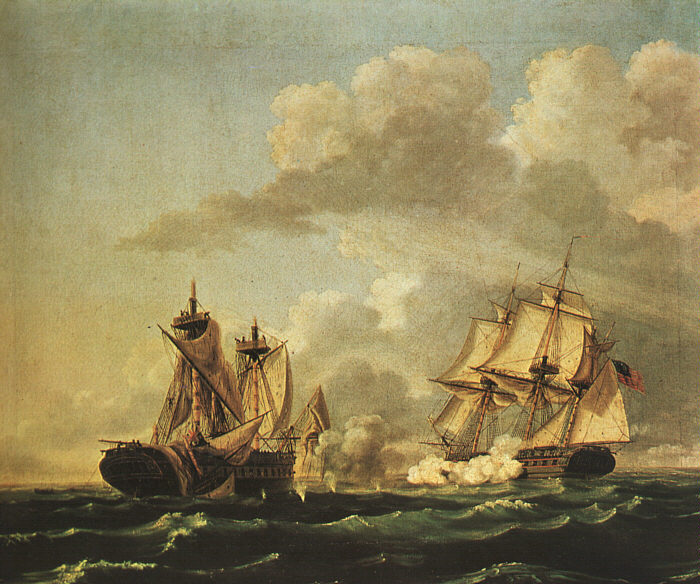

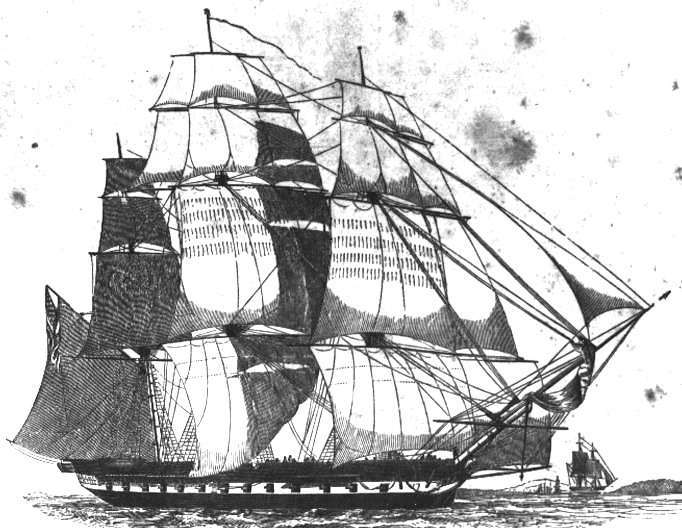

The full title is Thirty Years from Home, or a Voice from the Main Deck; Being the Experience of Samuel Leech, Who Was Six Years in the British and American Navies: Was Captured in the British Frigate Macedonian: Afterwards Entered the American Navy, and Was Taken in the United States Brig Syren, by the British Ship Medway of Samuel Leech. And I take issue with that title: because it advertises itself to be an account “from the Main Deck” around the War of 1812, a war memoir, I bought this book and read it. It isn’t a war memoir. Instead, it’s the life story of somebody who once served on the main deck. The war memoir portions may occupy a quarter of the book, and it’s in the most general terms—Leech keeps telling his readers to refer to newspapers if they’re interested. Seriously. A guy sits down to write his memoirs, and asks his readers to read the newspapers to get a sense of what it was like on the main deck. This undercuts the author’s authority by constantly cutting off when he almost provides insight into the day to day. Clearly not a great tactic. Today it would be like referring the reader to Wikipedia in the middle of your book, because you can’t be bothered to write your own book. In his defense, there are a few interesting paragraphs. I would quote them here so you wouldn’t have to read it, but I’m afraid it would tempt you to try and read the book. Help me help you not buy this book. Even at 99¢.

So, a fair question is what the book actually is about, compared to what it is advertised as? In the end, this book is less about what it says on the cover, and more about the author himself. The author only spends a few of those thirty years advertised on a ship—maybe five or six. The main focus of the book is what pet peeves Leech has: gambling, alcohol, lying, and flogging. He ignores what most Methodists would consider sexual sins, but maybe that’s because he’s trying to make his book “genteel”. He speaks from experience, so it’s easy to spot his biases. But he frames his statements as if he writes the truth, nothing but the truth, and the whole truth. For instance, in the case of flogging—which I am not into, for the record—he states that the public shame ruined every man who was flogged, then launches on a written crusade against flogging. Yet, he consistently gives us examples of flogged people who appear to have come out the other side mentally healthy. He draws a big comparison between the British ships he served on, which flogged heavily, and the American ones—he never mentions any American floggings. Yet, he never deserts from his flogging ships until the last one is taken in war and desertion is set up for him, while he deserts from his American ship later. He talks consistently about his desire to be at sea—most of the book takes place on land—yet takes few steps to get there. These incongruities built throughout the book and I was dissatisfied with my read. I kept reading hoping he would get back to sea, like he talked about, so I could read more about the differences in how American and British ships of the period were run.

The focus of the book rests on the author’s personal transformation from a heathen sailor to a Methodist Christian shopkeeper, and the title is misleading for that. From the Main Deck apparently refers to feeling guilt over buying and selling rum at his shop. Something like Baa Baa Black Sheep by Pappy Boyington has this moralizing element as well, but Boyington restricts himself to a few pages of that transformation, and focuses on writing his wartime memoirs. That’s a much more effective book and writing tactic than the one used by Leech here.

This is a bad book and I wish I hadn’t read it. I hope to someday find an interesting book from the main deck’s point of view in a man of war from this time period. But this author trusts too much in his audience’s familiarity with the normal, and ignores the title of his book in order to spend most of his time shilling for donations for his new Christian outreach organization. It wasn’t informative or gripping. It was rambling and navel gazing.

Labels:

1843,

History,

Memoir,

Napoleonic Wars,

Samuel Leech

16 September, 2018

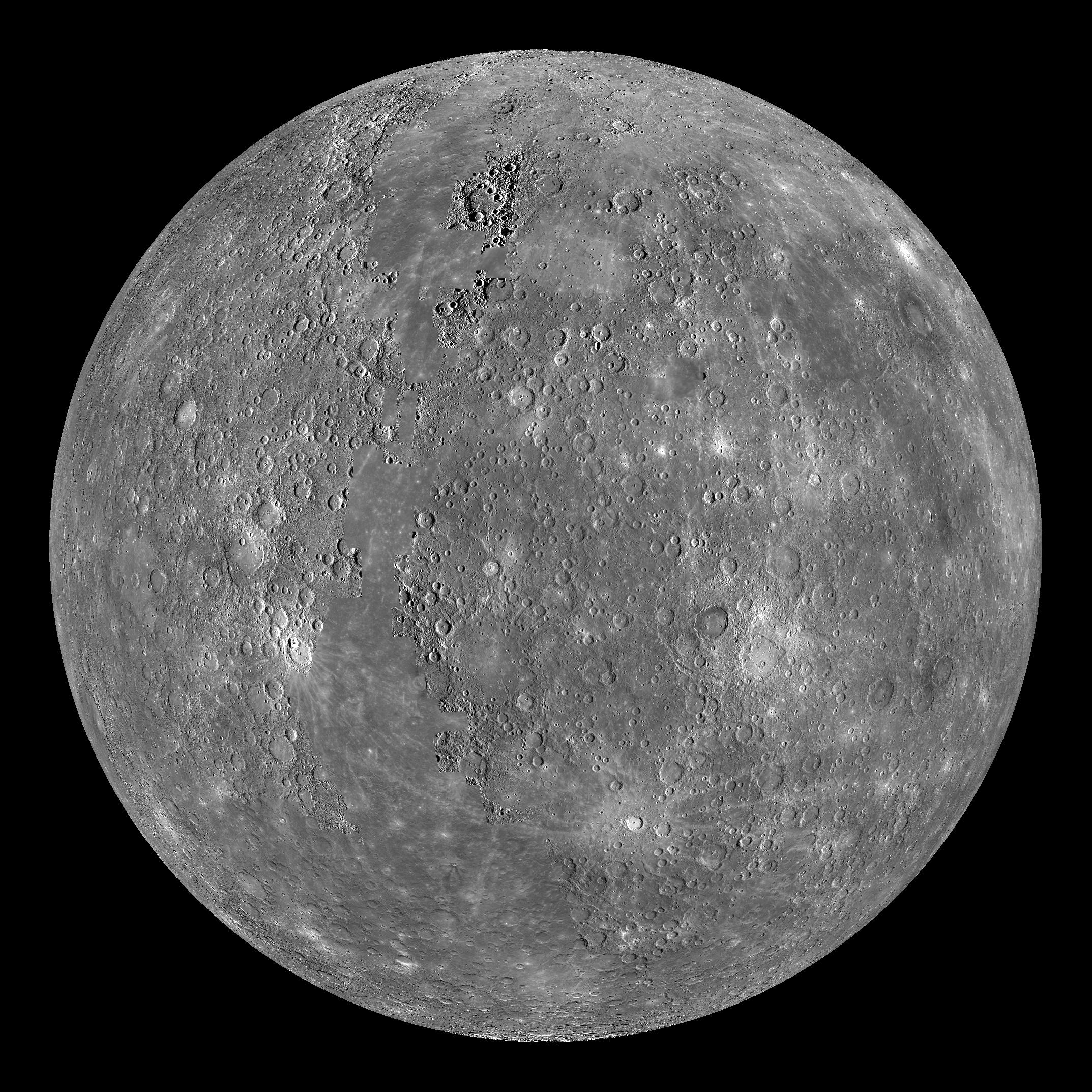

Sundiver by David Brin

I just finished reading Sundiver. This appears to be my first David Brin since 2015, when I read the two novels that come right after Sundiver—Startide Rising and The Uplift War. Those are both better than Sundiver. But that’s not to say that Sundiver is terrible. I did finish reading it and am glad I did. But I'm not sure I would ever recommend this book to somebody else.

The most interesting part to me is this theme that Brin runs through the whole book: integration into a technologically superior society. It’s a theme that mainly comes out in the worldbuilding Brin does. This novel’s story takes place shortly after human first contact with galactic powers that have been around billions of years. In contact, humans provide an awkward question for these elder species: where did humans come from? As there is no record of who nurtured humanity to sentience, they are known as a Wolfling species, a phenomena that is known but rare. It’s inconceivable to some species that humans evolved without outside influence, and who should be humans’ patrons? But combine their unknown past with two further backstory facts, and humans are not just rare, but unprecedented: fact one, humans discovered galactics, not the other way around; fact two, at the time of first contact, humans were already in the midst of uplifting chimpanzees and dolphins. This places humanity in a unique position that the hierarchical minded galactics have trouble conceptualizing. On the one hand, species who uplift others gain prestige. On the other hand, species who are uplifted by a long line of patron-client relationships, older species, gain prestige. The fact that humans have one but not the other makes them an awkward-at-best newcomer to the galactic community.

As a science fiction setting, this has some interest. But where Brin is brilliant is when he draws parallels to Europeans moving into North America, naming specific Native American tribes and historical figures. He shows how one tribe tried to fight traditionally and lost, another tried to integrate and saved their lives by losing their identity, another tried this, another tried that. He explicates what may be the most tricky political situation yet discovered by man, through using a space-based parallel. Should humans continue doing independent research when so much of the galactics knowledge is now available to them? Should they integrate as soon as possible, picking a patron species and letting themselves be uplifted into the galactic community? Should they retain their independence? It’s a fascinating study on Brin’s part. It’s really burning in my brain at the moment. (The other ideas all deal with human psychology and how we respond to trauma and work in groups. The main point with the human themes seems to be a sense that no matter what the tragedy, our responses should be our responses, not our ideas of how others respond.)

But the book can’t get out of its own way and explore this wonderful premise adequately. Integration is often ignored in the book, as a murder mystery takes up half of the book. And that’s the biggest problem here: the book doesn’t know what it wants to be, and probably isn’t playing to its strengths. There were three points that made me want to stop reading.

First, the writing in the opening couple of chapters isn’t great. It’s downright bad early on, but the story he is telling, and the ideas he introduces, are interesting enough to carry the clunky phrases and awkward sentences. So, though I contemplated stopping my read in the first few chapters, I didn’t. It’s obvious that Startide Rising had better writing, and I thought that writing was not great—but hey, this is his first novel, so it’s understandable that he gets better with practice. Good for him, not good for this book.

Second, the main character is a superman, and the rest are caricatures. Boring. I find that the journey the main character goes through to get over the trauma of losing his wife starts to hint at Brin’s later skill at character creation. But it’s not good enough here.

Third, the split in what this novel wants to be is awkward. It’s part galactic level politics and part murder mystery, both played out in a setting of a solar system research project. But the parts are too separate. After the reveal of Billibub’s crimes, the novel struggles to find its footing again. I looked down at what sounded like the end of the novel, saw that a quarter of the novel remained to be read, and wondered what in the world Brin would put in there. Then I felt that the continuation of the story of the solar ghosts was a bit of a let down after the action and whodunnit of the middle part of the novel. Of course, the murder mystery eventually returns as Brin’s detective got some things wrong, but the novel is still oddly paced. One quarter is about the ghosts, then half is about the murder and detective work, then the last quarter is largely about the ghosts, with a couple of chapters to resolve the murder mystery. This didn’t really hold together for me. It took some effort to get to the end.

In closing, on display here are some interesting ideas, but this book is only for fans of the universe, it seems. It’s a bad book. The pacing is inconsistent and offputting. The writing is painful at points. Plot elements are hamfisted. Yet the story shines in reflection, the pacing just got in its way. And Brin’s later ability to build good characters is almost on display here, but not quite. There is one engaging character thread, but things are not consistent enough to make me enthusiastic. The ideas and world building carry these negatives, for me. But in all, I wouldn’t recommend this book to somebody who does not like The Uplift War.

Labels:

1980,

David Brin,

Science Fiction,

Uplift Universe

11 September, 2018

Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer

A typical writing tactic is to reflect the character’s mental state with the writing mechanics. For instance, when a character goes crazy, the word choices, phrase lengths, and sentence structures follow: they all reflect this by being more imprecise, more inconsistent, and more convoluted. A crazy person’s narrator often pushes the boundaries of grammar and communication. Jeff VanderMeer doesn’t. When his biologist main character encounters the unknown it gets to her. But he doesn’t stop telling the story his way. VanderMeer writes short sentences. This is no Jack London. VanderMeer’s biologist pendulum swings to and from uncertainty throughout, but VanderMeer keeps his writing steady. Instead of using intentionally messy sentences, he uses imprecise terms, like “The Crawler”, to denote the unknown. His writing is precise in description, yet obscure in meaning.

That’s the main thing that stands out to me, his use of language and sentences. This is a story about the main character grappling with an esoteric mystery, and his writing matches. One example is that he applies multiple terms to the same set piece: the tower, the tunnel, two separate descriptions of physical size—one precise and one approximate—and what two different characters see—a biological organism or a concrete and shell built structure. In this way, the main character uncovers what she does of the mystery slowly, over time. As the terms shift back and forth, so does the reader’s understanding of both the set piece and the biologist’s mental state. So, rather than the sentence structures’ repetition becoming boring, the importance placed on the word choices lend inherent interest.

The whole is couched as a transcription of the biologist’s journal. She narrates the novel. Revealed near the end is the premise that these words are her writing out her journal after the fact, sitting up in the lighthouse and trying to communicate the prior few days. Her biologist’s training seems to affect the story as she describes, contextualizes, and attempts to synthesize hypotheses. She samples things and is just as confused about what is beneath her microscope as what is before her eyes. Much of the narrative deals with description. Like a biologist with a new species, as the story progresses, she slowly comes to terms with the unknown and unexpected. Beginning in a mental framework of familiar biological premises, her experiences and explorations lead her to unthinkable ends. It’s a slow process, even for a fringe biologist like herself.

Yet there is another half of the story, involving her now-dead husband. And this half VanderMeer holds away from the reader for the first quarter of the novel. I can see reasons for this: a wish to not overwhelm the reader right off the bat, a desire to allow the basics of Area X to be fixed in the reader’s mind, and the fact that the rest of the expedition is still alive for this part of the book, leading the biologist herself to cover up this half of the story intentionally. But by holding something away from the reader for so long, VanderMeer runs the risk of jarring them out of the narrative when it is introduced. Maybe the husband is a later invention of the writer, put there because of some perceived lack in the narrative, some perceived dissatisfaction with his own writing. Does it jar me? No. But for so much emotional weight and screen time, I’m not sure the payoff is there. Ultimately, the husband serves to set up the sequel. Sure, his presence does add some gravitas and some interest to the main character’s personality and mental anguish, but it seems a lot of effort for too little payoff. And if the main point of the story is the biologist overcoming her personal tragedies, which I don't believe, then the husband needed to be introduced much sooner in the novel.

The Area X part of the story is a mystery, inherently. Why has this shadowy governmental institution, The Southern Reach, shut Area X off from the world, and why are they interested in studying it? What is Area X? All we know by the end is that some sort of symbiotic, assimilatory relationship occurs there that exists outside of the normal human experience on earth. It’s mysterious and esoteric intentionally. The story is more that the biologist is coming to grips with the fact that there is mystery, than understanding any solution to that mystery. Is Area X’s origin and current state climactic in nature? Extra terrestrial? Nuclear or biological disaster? We don’t know. Neither does the biologist.

But what the writing, characterization, and story all work towards is the biologist growing in understanding of something she doesn’t discern at first. The coolest thing here, and the thing that the novel does best, is to show this process of coming to grips with the unknowable. You could read this book as a metaphor for religious experience, alien encounter, or the biologist dealing with the loss of her husband. In other words, any esoteric understanding or situation that changes everything. And VanderMeer portrays this wonderfully. The biologist starts out resisting the thought that things are changed, then she takes that thought way too far, then she reins it back in to what she considers a sensible response, all while she changes fundamentally. It’s a gripping journey, and one that uses science fiction to help explain what is fundamentally a universal experience. In this thread, it reminds me of Embassytown, by China Mieville—a favorable comparison as Embassytown is a great novel to me.

The focus of the writings rests on description and internal monologue. Though there is some action—one chase, one murder, the discovery of two bodies, and one attack by an unknowable creature—most of the story is the biologist either walking around getting freaked out, or sitting down getting freaked out, and thinking about things. VanderMeer uses internal monologue to ramp up the tension and there are more psychological crises than physical ones. More close calls that satisfying action scenes. This ruminatory focus isn’t inherently a problem, obviously, unless he writes physical action better than psychological action. But I did find myself slightly wishing that something meat and ballistics would occur more often than just walking down a set of stairs, or across a beach, or up a lighthouse. Slightly, I emphasize. And probably only because there is so much implied action that occurs off scene. VanderMeer says that so much has happened off scene and does not show it to me. I think I wanted a little more on screen. One or two more actions. Less buildup for actions that are averted. But this story being the biologist’s journal means that VanderMeer probably wants to reinforce the mystery by having the biologist confused how half of her squad died. It works, but may not have been more than a good tactic.

So, since the words focus on what’s happening in the biologist’s head, I should at least mention some of the themes she’s thinking about: mortality, perception, wildlands versus areas humans live, interpersonal relationships, the status of self during upheaval, the ecology of areas between other areas, spirituality (lightly), morality (also, lightly), and the nature of linked relationships like a marriage, or expeditionary squad, or coworkers. These are a lot of themes. VanderMeer focuses on perception and mortality, relationships and self, ecology and mystery. And I am curious about where he will take these themes. But the main theme here is how humans approach mystery, how we categorize and dissect the unknown, and how we react when our normal processes don’t pay off. VanderMeer shows that to approach something sublime necessarily changes us, like the biologist left alive at the end of the book, or we try our best to ignore it, like the murdered surveyor.

In closing, this somewhat Lovecraftian tale is good. It’s dark and tragic and I’m not sure I want to read more in this series. There are two other books dealing with The Southern Reach, but I like the mystery so much that I’m not sure I want to know more about it. I appreciated his writing and will probably read another novel by him, but not next. I usually appreciate more complex sentences than this. I would compare this novel to Embassytown in humans approaching the unknowable, and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress in the main character narrating the tale. But I find Mieville to be something I want to reread more, and Heinlein allows his characters more influence over their tale. This is a good book, but not great.

Labels:

2014,

Horror,

Jeff VanderMeer,

Nebula Award,

Science Fiction,

The Southern Reach

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)