03 August, 2015

2001: A Space Odyssey by Arthur Clarke

1. One thing that I really enjoy about Clarke, both here and in Rendezvous with Rama, is his ability to give information in a way that laymen can understand and enjoy. This might be my bias of loving layman's physics, but here it interests me. This could be some pretty dry stuff—explaining slingshoting spaceships—but it works here. He finds that line between too much information boring the reader, and just enough information told in an interesting way to make learning enjoyable.

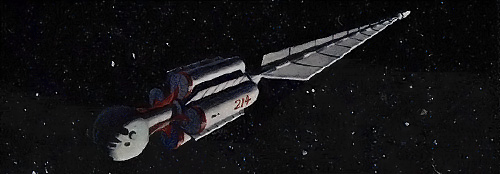

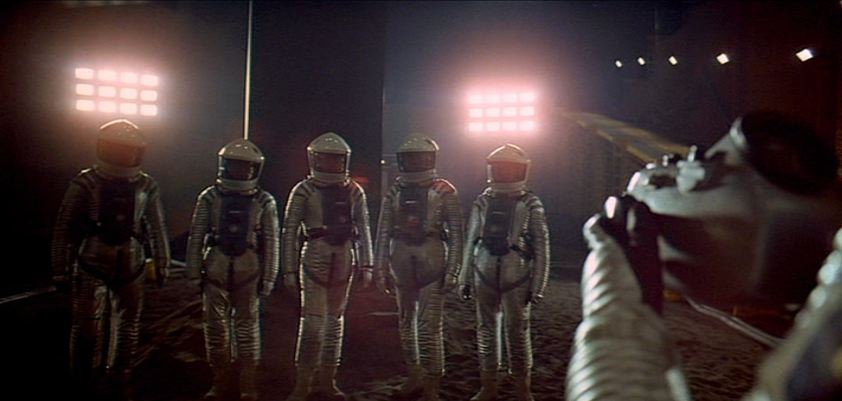

2. While he does this with physics, the detailed description of life aboard the spaceship is a bit boring. It is an incredible feat of imagination—even for Clarke, who is known as a fantastic predictor of the future—but it seems to drag on, much like the days must drag on for the two astronauts who are awake.

3. HAL is a great character. He ends up being so human in his panic, his difficulty to maintain a lie, and his return to childlike behavior—all while still being unavoidably computer. He believes that all people must be like him because he is the only existence he knows. This is a powerful character, and an effective emotional tragedy.

4. HAL's fault—the conflict of lying about the mission to the astronauts, then concluding that these instructions to lie must indicate that the astronauts are nonessential—is a beautiful moral metaphor, and convincing examination of future technology. Like much science fiction, Clarke examines a current thread in culture—AI and space travel here—and pushes it to a logical extreme to show both potential benefits and pitfalls. The basic premise that shakes out is the truism that humans know not what they do. By not knowing how HAL will develop, they know not what their creation will do. Here Clarke could have gone the pulp route and made HAL a secret villain delighting in punishing and testing the meatbags. But instead I empathize with HAL. He is a well developed character. His flaws are part willful and part ignorance and part situational, much like mine tend to be once I fully glimpse them.

5. The scope of this book is fearless: tackling a timeline from pre-human to post-human. I think Clarke pulls it off, which is amazing. He is a confident, talented author biting off a huge chunk of material, and getting it to do exactly what he wants. And he does it well. This is an episodic novel without a frame narrative, but this structure actually works here because the thread is so important to each episode. Human evolution and change is that thread, and it is central to every part of the book. Even the opening pre-human part is the same narrative as the other parts. The echoes come back in situations so different from the original that they offer new insights and the theme rolls along, keeping it all together. This tactic of a central theme tying all of the episodes together would have helped Foundation, where the central eponymous element changed so drastically between episodes that the novel felt disjointed.

6. As to that first part, the pre-humans are described with an empathy that is touching. What we take for granted today, their great leaps of logic, are almost as astounding in the showing as they could be. I think merely telling about them would have lacked power, but there's just enough telling to ensure and confirm that the reader is on the same page with the author and characters.

7. Clarke's world building here is amazing. But most of his characters are merely good. In this way he's almost the opposite of Heinlein: whose characters are great, but whose world building is not as perfect as they are. I am not saying that Clarke's characters are bad, they're just not as perfected as his world building.

8. At the end, I want more. Star Child blowing up the satellite is such an enigmatic and powerful act that I'm looking forward to seeing how this post human goes, and what it does. The contrast between it and humanity is so great that I'm interested to see if it becomes a god, and what humanity does next. The temptation is obviously there narratively for Star Child to assume divinity. But if there's one thing that I know about Clarke, it is that he foils whatever I predict he's going to do, then shows why what he came up with is more logical and correct.

9. Clarke's writing is not amazing, but it is good. His teaching moments are very good—and I think it is a special, valuable talent to be good at making orbital mechanics interesting. But he does have moments of brilliance here, the high point being: "Sorry to interrupt the festivities, Dave, but I think we have a problem." This is just one example, but it is so great! Overall, this is above average writing with moments of brilliance.

10. Another place where Clarke bites off more than the average author can chew is in the nearness of his future—this is not thousands of years hence; it is something he will probably see in his own lifetime. [He did live through 2001 and the intro to the audiobook that I listened to was really enjoyable, reflecting on what he got right and wrong, the way the book was written, and its influence.] It is courageous to try this. And although there are some clear differences between his work and how the future actually shook out—we have no AI, the human body requires a lot more exercise in space than he anticipated, we have yet to attempt artificial gravity in space, we have sent no manned missions farther than the Moon, etc.—he pulls the whole off well enough that it does not feel dated to me. Reading space travel stories by HG Wells or Jules Verne is difficult today, because all of the disbelief that must be suspended to buy into the narrative. Not so here. This is easy. 2001 has become alternate history since it was published, but it still works well.

Labels:

1968,

Arthur Clarke,

Science Fiction,

Space Odyssey

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment