1. Compared to

Banks' other

Culture novels, this one has few characters. Like

Inversions, the story closely follows the main characters. Here, the main characters are Turminder Xuss and Djan Seriy Anaplian, Ferbin and Choubris Holse, and Oramen and Neguste; while Tyl Loesp,

Liveware Problem, and Tove are the three secondary characters that matter the most. There are a ton of other characters, but they’re in and out to reflect the main characters and provide other points of view about the central discussion of the novel. And that’s what Banks is doing: focusing on the main characters, and using the others to provide plot points, context, and story movement. Where in

Excession he revels in tons and tons of characters, this novel has comparatively few. But it doesn’t detract from the scope of the novel: the scope is still satisfyingly complex and varied. I say satisfyingly because the discussions are wrinkled, varied, and deepened through the diversity of examples given in the novel. The dozens of tertiary characters contribute directly to the scope of the novel, while the six main characters keep it focused on the discussion of the novel. This shows Banks thinking deeply about what he includes and writes. It’s a tight, well done choice.

People craved self-importance; they longed to be told they mattered as individuals, not just as part of a mass of people or some historical process. They needed the reassurance that while their life might be hard, bitter and thankless, some reward would be theirs after death. Happily for the governing class, a well-formed faith also kept people from seeking their recompense in the here and now, through riot, insurrection or revolution.

A temple was worth a dozen barracks; a militia man carrying a gun could control a small unarmed crowd only for as long as he was present; however, a single priest could put a policeman inside the head of every one of their flock, for ever.

2. The way the novel converges successfully signposts the ending. This works because drawing the main characters closer together increases the tension—I mean, something has to happen when all the main character get together. He also did this in

Excession, but it works very well here because the reader knows it’s coming and he draws it out a bit, allowing that feeling in the reader of knowing more than the characters and agonizing over the characters’ choices because of it. In

Excession, everybody comes together except

Sleeper Service; then when

Sleeper Service finally makes a run for that common location, it surprised me a bit: I didn’t see the story set on

Sleeper Service relating too closely, until suddenly it did. Here, all three of the main character pairs are immediately linked through their familial connections, while the three secondary characters are also connected to that family—though

Liveware Problem only through Special Circumstances. This immediate connection allows Banks to tell three different sides of the same story. The closeness of the connection means that there isn’t a separate epilogue for any character after the climax, they are all resolved at one go, in the climax itself. This provides a satisfying finish to the plot and allows the epilogue to touch on the central story itself.

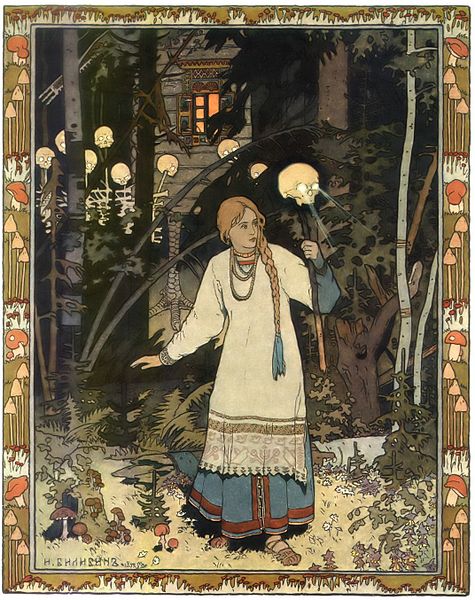

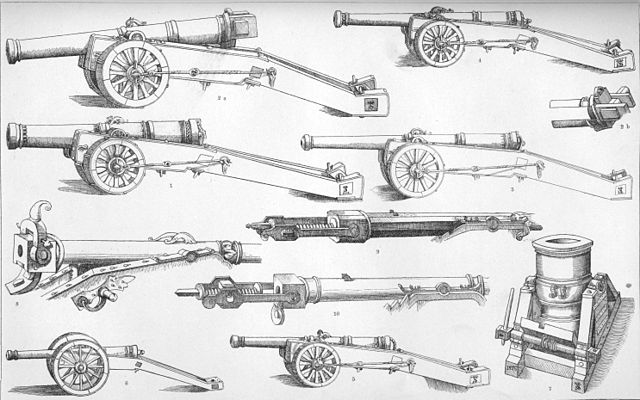

3. This novel is a direct mix of fantasy and science fiction.

Lord of Light mixed fantasy language into a science fiction story.

Inversions told a fantasy story with a science fiction ah-ha moment. This is both, simultaneously and successfully. Here, the Culture deals with societies that are much less advanced than it in general—hence Contact and Special Circumstances. In other words, there are spaceships flying over pike and shot battles. Where

Inversions told its story from the side of the contacted, this tells both sides of the story at the same time—both contactee and contactor. And that, as a fan of the series, is a wonderful exploration of Contact.

4. However, though this fan service of exploring a contact situation more deeply is the basis of the story, the novel is not fan service. The theme, and it’s very prominent, is power. Power is the theme, but it’s also the main goal of each character, and drives the plot and story forwards. This triple focus of power shows just how prominent the theme is. Some novels have two themes: one for the story and one for the reader. This novel has one in three tactics: but it doesn’t grow dull because Banks discusses power from multiple points of view. Even just Ferbin and Choubris Holse’s conversations would be enough for me to state that this novel is about power, but Banks allows the theme into every other nook and cranny.

“Still, it is often easier to be the second in command, prince,” Hyrlis said. “The throne is a lonely place, and the nearer you are to it the clearer you see that. There are advantages to having great power without ultimate responsibility. Especially when you know that even the king does not have ultimate power, that there are always powers above. You say [the assassin] was trusted, rewarded, valued, respected . . . Why would he risk that for the last notch of a power he knows is still enchained with limitations?”

The above dialogue example shows how Banks is wrinkling and sustaining this discussion of power: through the characters. Like so many of these characters, Hyrlis is only on-scene for part of one chapter, then gone. Hyrlis exists only in his importance to Ferbin and the theme: nothing else. Like Hyrlis, all of the tertiary and secondary characters reflect the main characters and contextualize the central question, while each of the main characters is simultaneously attempting to locate power, or navigate it. Power is their driving force whether it’s what they want or what they’re reacting to.

That had always been his father’s ultimate aim, Oramen knew, though Hausk had known that he’d never see that day – neither would Oramen, or any children he would ever have – but it was enough to know that one had done one’s bit to further that albeit distant goal, that one’s efforts had formed some sturdy part of the foundations for that great tower of ambition and achievement.

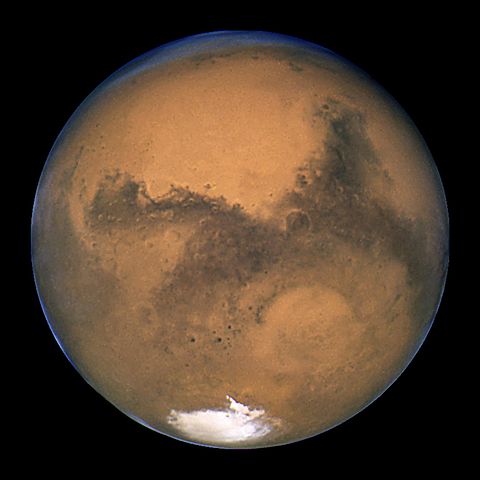

The stage is small but the audience is great, had been one of King Hausk’s favourite sayings. To some degree he meant that the WorldGod watched and hopefully somehow appreciated what they were doing on its behalf, but there was also the implication that although the Sarl were primitive and their civilisation almost comically undeveloped by the standards of, say, the Oct (never mind the Nariscene, still less the Morthanveld and the other Optimae), nevertheless, greatness lay in doing the best you could with what you were given, and that greatness, that fixity of purpose, strength of resolve and decisiveness of action would be watched and noted by those far more powerful peoples and judged not on an absolute scale (on which it would barely register) but on one relative to the comparatively primitive resources the Sarl had available to them.

In a sense, his father had told him once – his contemplative moods were rare, so memorable – the Sarl and people like them had more power than the ungraspably supreme Optimae peoples with their millions of artificial worlds circling in the sky, their thinking machines that put mere mortals to shame and their billions of starships that sailed the spaces between the stars the way an iron warship cruised the waves. Oramen had found this claim remarkable, to put it kindly.

Above, Oramen contemplates his father’s goal, the theme of his father’s life. And guess what? It’s power. This contemplation is him attempting to come to terms with his power by learning from his father. But the only reason Oramen does contemplate this is because he believes his brother and father are both dead, making him the Prince Regent. Being the one about to be the king causes him to start contemplating this question. And this brings up my third point about how Banks supports his theme: power and power-plays drive the plot and characters forwards.

The Sarl would achieve a goal they had been pursuing for almost all the life of their departed king, the Deldeyn would be defeated, the loathsome and hated Aultridia would be confounded, the WorldGod would be protected – who knew? even saved – and the Oct, the long-term allies of the Sarl, would be grateful, one might even say beholden. The New Age of peace, contentment and progress that King Hausk had talked so much about would finally come to pass. The Sarl would have proved themselves as a people and would, as they grew in power and influence within the greater World and eventually within the alien-inhabited skies beyond, take their rightful place as one of the In-Play, as an Involved species and civilisation, a people fit – perhaps, one day, no doubt still some long way in the future – to treat even the Optimae of the galaxy (the Morthanvelds, the Cultures, and who knew what alien others) as their equals.

More than simply assassinations and fights, Banks realizes here that power is what contact is all about—contact being the process of the advanced Culture contacting a more primitive society. Hence the weird dancing around the Morthanveld, hoping to not step on any toes so that when the Morthanveld are finally High-Level Involveds, they will be a close ally of the Culture. Therefore, any contact with them is highly regimented and questions of power define how characters interact with the Morthanveld throughout. Myriad and funny and diverse examples of contact that are spread throughout wonderfully contextualize the central question, but in the end the discussion of power is, appropriately enough, tied off by the plot and story, not some lengthy closing oration. The plot itself, as it does in so many stories, shows the conclusions Banks draws from the theme: namely, power is simultaneously a benefit and a curse, always, no matter how much of it you have, yes even over your own self or a small part of your own self, and no matter how moral or amoral, ethical or unethical you are in using it. The whole novel begins and ends about power: from the assassination of the opening through the struggle for power on and off the planet at the end, this novel is about power and that question drives plot, story, character, and discussion to a satisfying level. I’m still interested, at the end, in discussing power, despite having just read 593 pages of discussion on it. That’s a testament to how wrinkled, diverse, and varied Banks allowed his theme to get. As always, on this site I’m not going to go into what Banks says about power, just how he says it. But I look forward to discussing these ideas and hierarchies with people.

5. And that writing! I mentioned the plot above, contrasting it to a closing oration, but the two closing orations are actually spectacular: “Oh go and fuck yourself,” closes the novel and “Ah, family life, eh?” closes the epilogue. Obviously, Banks still uses that wonderful, contrasting, colloquial and formal back and forth—as described in

my notes for Excession. But here, he re-injects some of the gorgeous language found in the mouths of aliens in the first two novels. However, instead of the lengthy oration in

Consider Phlebas—

see long quote in point four of this link—here there are lines and paragraphs spread throughout that just make me stop and stare.

“What fleeting titillations life continues to throw up, many-fold.”

+++

This is how power works, how force and authority assert themselves, this is how people are persuaded to behave in ways that are not objectively in their best interests, this is the kind of thing you need to make people believe in, this is how the unequal distribution of scarcity comes into play, at this moment and this, and this . . .

+++

“Power over others is the least and most of powers, betruth. To balance such great success with transient lack of same is fit.”

And this last example comes out of the mouth of an Oct. Through the Oct and other alien species, Banks varies his writing immensely: each has their own voice. For instance, that second quote above is a Culture citizen internal monologuing. Here is how an Oct talks:

“Oramen-man, Prince. That who gave that you might be given unto life is no more, as our ancestors, the blessed Involucra, who are no more, to us are. Grief is to be experienced, thereto related emotions, and much. I am unable to share, being. Nevertheless. And forbearance I commend unto you. One assumes. Likely, too, assumption takes place. Fruitions. Energy transfers, like inheritance, and so we share. You; we. As though in the way of pressure, in subtle conduits we do not map well.”

The Oct place verbs at the ends of sentences, they imply connecting words and subjects, they speak in phrases of probability. And the rest of the alien voices Banks uses are also changed from the Culture's and narrator's voices. In short, I love it. The wonderful colloquially formal language the Culture tends to speak is polished here, but it’s also contrasted with alien patterns and word choices that keep the novel’s writing changing, exciting, and varied. So far, this is the best writing I’ve read from Banks—the most engaging and consistent. He keeps getting better.

6. The buildup to the ending works well here, unlike the too lengthy ending to

Consider Phlebas. Where

Consider Phlebas drags out the buildup to the ending—it simply takes too long and I got bored—here he pulls out the buildup a ways, but not too far. Having the characters still coming together towards the end allows Banks to jump between them and resolve smaller threads in their stories before converging them and ramping up the converged action for a couple of chapters to the end. This tactic allows the ending to be more diversely set and charactered, giving it a variety that keeps me interested and the novel well paced.

7. The pacing of the whole story sticks to a typical tactic that I’m really starting to enjoy when it’s done well: the pulp fiction tactic of ending each chapter unresolved, then moving to the next chapter’s fairly slow opening and different character and location. It isn’t heavy handed click-bait type writing—it’s not that pulpy. Where the series

A Song of Ice and Fire is pulpy with the way chapters end by implying main characters are dead, and then they aren’t; here, when Ferbin finally sees Djan for the first time, the chapter ends right after he realizes who she is. The next chapter is not about them, but once it gets back to those two a couple of chapters later, it opens with them hugging and beginning to talk. This chapter structure helps structure the whole novel and keeps the whole thing exciting.

_-_03.JPG/360px-Licenciado_Gustavo_D%C3%ADaz_Ordaz_International_Airport_(2014)_-_03.JPG)

8. In all, this book impresses me immensely. Banks thinks deeply about his writing and he is so skilled that the whole book is incredibly tight—like how chapter pacing ties into book pacing, or theme ties into every level of the novel. This is a feat of storytelling. It’s exceedingly well constructed. It’s also well written—the language is wonderful and wonderfully varied. But it’s not all a writer’s treat: it’s an exciting novel that held my interest through both the story and the theme—not just the writing and construction. The novel stands well on its own, with no other Culture novels being read first by the reader. In all, this is easily my second favorite Culture novel, and could be as good as

The Player of Games. The two novels are so close in quality that I would have to read both again in order to tell which I like better. And I look forward to that! Right now, I think they’re essentially indistinguishable. Masterful book.

He had already asked the Nariscene ship why it bore the name it did.

“The source of my name,” the vessel had replied, “The Hundredth Idiot, is a quotation: ‘One hundred idiots make idiotic plans and carry them out. All but one justly fail. The hundredth idiot, whose plan succeeded through pure luck, is immediately convinced he’s a genius.’ It is an old proverb.”

Holse had made sure Ferbin was not within earshot and muttered, “I think I’ve known a few hundredths in my time.”

.jpg)

.jpeg/640px-FMIB_37108_Escadre_de_Vaisseaux_a_Trois_Points_(1940).jpeg)

.jpg/640px-China_-_Emei_Shan_9_-_misty_mountains_(135961844).jpg)

.jpg/640px-USS_Florida_(SSGN-728).jpg)

.jpg/640px-United_Nations_General_Assembly_Hall_(3).jpg)

_-_03.JPG/360px-Licenciado_Gustavo_D%C3%ADaz_Ordaz_International_Airport_(2014)_-_03.JPG)